When George Romero sadly passed away in July of 2017, it is fair to say the news left film fans in mourning and specifically horror fiends. Famous for his flesh-eating and satirical Dead trilogy – which would eventually become a six-film anthology by 2009, he was a filmmaker who refused to be pigeon-holed (as the films in this set will attest). Before Dawn of the Dead (1978) and Martin (1978) he completed three other features. It is these – There’s Always Vanilla (1971), Season of the Witch (1972) and The Crazies (1973) which were lovingly restored and presented in a box set by the wonderful folks at Arrow Films and their Video label.

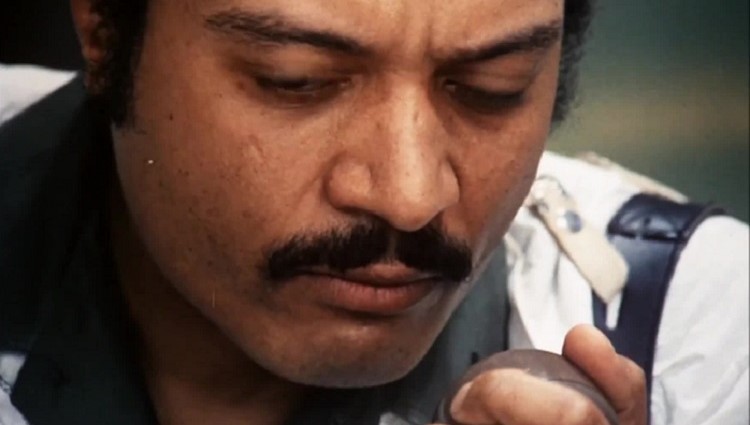

There’s Always Vanilla AKA The Affair was the first film made by the team behind Night of the Living Dead (1968) and was fraught with problems from the start of its troubled production. It is not so much a film directed by Romero – his style is barely recognisable – than superbly edited making the most of a flimsy plot. The film centres around a love story during the 70s in which sexuality was liberated and countercultural, clearly inspired by Mike Nichol’s The Graduate (1968) and Larry Peerce’s Goodbye, Columbus (1969) which had been released a few years before. Chris (Raymond Laine) loves Lynn (Judith Ridley) and she loves him until… they don’t, she’s a commercial actress and he’s struggling to find a niche following time served in the army.

The film was carved from a short showreel meant for Laine (a dead-ringer for a young Russell Crowe) and while the crosscutting and juxtapositions are rather heavy-handed, – and the first half feels somewhat aimless and laboured – …Vanilla‘s an interesting look at the experimental cinematic mood – it captures an essence of the era. Granted, with some horrendously dated gender labels and stereotypes. There is a hint of the director during the sinister and sleazy abortion scenes in which canted camera angles and filters are employed and an ominous soundtrack plays.

There’s Always Vanilla, so named for the lead character’s father’s analogy for life – the more exotic flavours tend to be discontinued or hard to locate, you see but there’s always… well, you get the drift. The pretty metaphor within the ending which we also see at the film’s opening brings it full circle and attempts to convey the alleged freedom and liberty of the decade, or perhaps it’s also a state of mind; you’re only free if you believe you are – deeply philosophical questions for a film that started life as a showreel. While the film is dated and technically flawed, it really captures a mood and authenticity of a period and the beginnings of a filmmaker and his team at the genesis of their craft.

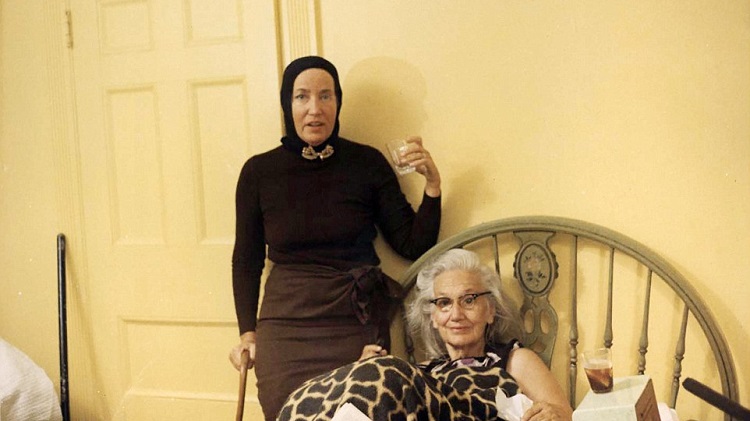

Season of the Witch AKA Hungry Wives (awful) or Jack’s Wife (working title) fares better. Made in 1972 and revolving around housewife Joan Mitchell (Jan White) and her eventual dabbling in the occult, courtesy of a few tarot card readings, before accepting her place in a coven. What strikes most with this film is the level of sophistication in comparison to …Vanilla. Still prevalent are some technical flaws however, from the Buñuelian and atmospheric opening to the depiction of female disillusionment within the narrative, this film is fascinating.

It isn’t necessarily about magic but rather how a woman – who wants more beyond marriage and motherhood – wishes to embrace her independence and sexual prime, and take back some power through witchcraft (almost depicted here as a completion of womanhood). One can see its distinct influence on Anna Biller’s fabulously feminist The Love Witch (2016). Using themes of oppression and transgression, it is no accident that this film’s existence stems from the period of women’s lib – patriarchy manifested as a demon-masked man on the prowl, personifying Joan’s fears, albeit within a recurring dream sequence – while fragile and toxic masculinity personified through the characters of Jack Mitchell (Bill Thunhurst) and Greg (Raymond Laine).

Season of the Witch is a gem of a film, from its avant-garde opening to the interesting depiction of gender roles coupled with the enigmatic and nuanced performance of Jan White. It feels like a primer for Martin with its political progression, religious motifs and the use of the colour red (although to differing effects).

This use of chromatic is also prominently used in The Crazies, a science-fiction-horror-thriller in which a small American town is quarantined following the accidental release of a biological weapon. The Army have “everything under control”, at least they certainly want everyone to believe they do – reinforced by a non-diegetic military drumroll punctuated sporadically throughout. We, along with the townspeople are on a need-to-know basis as all hell breaks loose and national security becomes a real concern.

We’re subjected to horrifying images as people are dragged from their sanctuary of Church or a small group of individuals are backed into a stand-off, threatened by gunfire. Then, there’s the scientist who makes a breakthrough with an antidote (the soldiers have all been inoculated first with what little antibiotics they have) only to be murdered, his vials of life-saving serum (red again) smashed around him. David (W.G. McMillan) and Judy’s (Lane Carroll) arc pulls at the heartstrings and, a few pacing issues aside, it is them we root for.

Watching the films in this boxset in chronological order shows a distinct progression in the New York native/Carnegie Mellon alum’s filmmaking. The man who made films (whether writing, directing or editing or a combination of all three) instinctively, was politically progressive, possessed a sense of humour and rarely wrote characters that weren’t multi-faceted. He depicted a rare equality within male and female characterisations and did not exploit or resort to sex.

Mr. Romero, George, you are sorely missed.

This box set of his early works between Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead – see what they did there? is replete with extras and special features and is a must-buy for any fan. He was still developing his style and craft and the films may not strike as much of a chord as the ones that followed*, however, there’s still much to enjoy and appreciate. Season of the Witch, and the Guillermo del Toro interview with George – which is a wonderful and joyous watch – are worth the purchase alone. Alternatively, all three are now available individually via Arrow.

*”My stuff is my stuff. Sometimes, it’s not as successful as my other stuff but it’s my stuff.” (G.A.R, 2011)