It was the film listed on the marquee of the local cinema as George Bailey (James Stewart) ran through a snow-covered Bedford Falls, and back into the bosom of his family. It was also the picture that Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) took Kay Adams (Diane Keaton) to see at Radio City Music Hall on their first date. Aside from being dearly beloved by filmmakers named Francis, The Bells of St Mary’s does what very few films have been able to do, and that is out-charm its cinematic predecessor (despite Bosley Crowther’s 1946 claims in The New York Times).

Father ‘Chuck’ O’Malley (Bing Crosby) was first seen in Leo McCarey’s 1944 hit Going My Way and is reintroduced here – wearing his straw boater on a jaunty angle – arriving at St. Mary’s in order to help Sister Superior Mary Benedict (Ingrid Bergman). She, who is fighting to keep the Parochial school open and out of local businessman Horace P. Bogardus’ hands. Bogardus (Henry Travers) has already purchased the adjacent building to St. Mary’s but is determined to secure the school grounds for his parking lot.

In the beginning, Father and Sister clash – albeit with a twinkle of the eye and a sly smile on the face, alongside quips like: “Did anyone ever tell you, you have a dishonest face? For a Priest, I mean.” Somewhat predictably, they – the American Priest and European Nun – realise they must come together to fight a common goal. Sound familiar? Okay, so it’s not fascism per se but the film was released in December of 1945 so it’s hardly a stretch to see its themes set against the war effort.

Director McCarey had a somewhat varied career, dabbling in slapstick (Duck Soup, 1933), melodrama (Make Way For Tomorrow, 1937), screwball comedy (The Awful Truth, 1937) and romance (An Affair to Remember, 1957). He would make four Priest-led films (Going My Way, …St. Mary’s, My Son John in ’53 and The Devil Never Sleeps in ’62), which for a devout Catholic is hardly surprising, but in all and especially in this film he managed to humanise both Priests and Nuns, depicting them as flawed individuals and, crooner Crosby and the radiant Bergman take Dudley Nicholls’ script and run with it.

There are no villains of this piece – Travers best known for playing angel Clarence in Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life is probably the most antagonistic, however, manages to convey sincerity and humour all the while attempting to chuck the Sisters and their young wards out of their school. While this is the overarching plot, there are minor, almost irrelevant arcs which provide the gentle comedy and at times offer the most laughs, which go to the heart of the film and viewer alike. Like, flunking student Patsy Gallagher (Joan Carroll) who leans on Father Chuck to help her pass the school year.

Patsy is left at St. Mary’s while her mother Mary (Martha Sleeper) weighs up giving caddish pianist Joe (William Gargan) – who left her pregnant and alone – another chance. Or, bullied Eddie Breen (Richard Tyler) who has been “turning the other cheek” as per Sister Superior’s advice until she decides to teach him, in one memorable and hilarious scene, to box. Even when Chuck and Mary Benedict do have a difference of opinion, it is all decidedly good natured.

It is these threads, and elements within the mise-en-scène, which show the passing of time as the seasons change and the school year progresses, culminating in the most adorable Nativity performance, in the history of Nativities. McCarey was all about improvisation and naturalism in his actors’ performances, and it is no more apparent than in the recreation of “Jesus’s birthday”. It was reportedly shot in just one take with the children encouraged to ignore the camera and crew, and approach their material as they saw fit.

This is an aspect of McCarey’s work ethic which admirer Yasujirō Ozu emulated in Tokyo Story – the 1953 retelling of Make Way For Tomorrow. It is a characteristic which make this film so utterly charming. There are of course – given Crosby’s presence – musical numbers, courtesy of composer Robert Emmett Dolan, such as the delightful “Aren’t You Glad You’re You?” and even Bergman stretches her vocal chords in her native Swedish for “Varvindar Friska” (Spring Breezes) and while musicals are not everybody’s cup of tea (I know, who doesn’t love a bit of Bing?) there are ample numbers to enhance the narrative yet few enough not to put people off completely.

Drill deeper and there are interesting depictions of the gendered approach to conflict which one may argue are outdated, however, some still ring true even today. Yes, it may offer an idealised, even sweet depiction of Catholic schooling but this assertion of patriarchal power is more than still relative especially in the institution of the Roman Catholic Church, and indeed, as discussed by Revd Steve Nolan’s analysis in the disc extras – the notion of paternalism. Made obvious in the way Dr. McKay (Rhys Williams) decides to withhold vital information of and from a (female) patient but discusses freely with ‘a man of the cloth’.

Although not necessarily a Christmas film, you can do a whole lot worse than including this film on your festive watchlist (if not before). It’s the perfect addition containing humour, charm and sincerity, and one which warms the cockles in much the same way as The Shop Around the Corner or Remember the Night. It may not be regarded as McCarey’s most cinematically satisfying film but its popularity is evident and understandable.

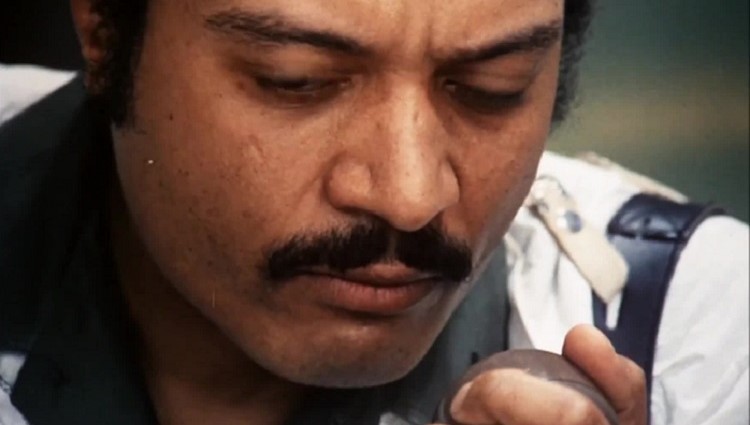

The performances are natural, subtle and nuanced especially Bergman who was rarely seen onscreen less than glamorous, and was loaned by David O. Selznick as part of a deal he struck with McCarey. Here she shines, quite literally, from the glow of her unmade-up face to the luminosity of her smile and the clever use of lighting which flawlessly renders her, hitting the eyes perfectly within her wimple. Made all the more noticeable here thanks Paramount’s restoration process which still contains some grain but which creates a beautiful monochromatic sheen to each frame, set within a 1:37:1 aspect ratio.

The Bells of St. Mary’s will charm your socks off – and it’s a well-known fact that this writer watches it every Christmas Eve without fail. It just ain’t Noël without that little boy, Bobby (Dolan Jr), knocking on a curtain introducing himself in one breath, “This is Mary and I’m Joseph, and we came to Bethlehem to find a place to stay.”

Special Features

It’s almost a given now that if it’s an Arrow Films release, the Academy label in this instance, there are always a few extras to enjoy after the credits have rolled… and only then.

Up to His Neck in Nuns (22 mins) – This visual essay by David Cairns is entertaining and informative as the writer dips into Leo McCarey’s filmmaking history, his early life, Catholicism and heavy drinking. It switches from film clips, stills, photos, archival interview quotes, and Cairns’ lovely Scottish lilt ensures it’s never boring.

Analysing O’Malley (19:48) – This appreciation by the Chaplain of Princess Alice Hospice, film academic, and author of Film, Lacan and the subject of Religions: A Psychoanalytic Approach to Religious Film Analysis, Revd Dr. Steve Nolan is a little dry in comparison to the previous essay. Nolan sits to the right of the frame and narrates; reading an essay from an autocue. It’s a fascinating analysis but one which would have worked just as well as a commentary (surprisingly lacking here).

You Change the World (32:07) – This short religious propaganda film was shot by Director McCarey in 1949 and features appearances by Bing Crosby, Bob Hope, Irene Dunne, William Holden, Loretta Young, and Jack Benny – all regarded at the time as ‘super Catholics’. It’s arguably some of the best acting any of them have ever done, and they’re playing themselves! It’s preachy, condescending, cringeworthy hypocrisy at its finest (and I say this as a Catholic). The purpose of the film was to persuade “good, decent, normal people” to join The Christophers. I stopped counting how often “The Declaration of Independence” is mentioned when I reached ten.

Two Screen Guild Theater Radio Adaptations: One from August 26th, 1946 (29:52) and the other recorded October 6th, 1947 (28:59). Both star Bing Crosby and Ingrid Bergman reprising their roles as Fr. Chuck O’Malley and Sister Superior Mary Benedict. The radio programmes are played over a slide show of film stills.

Musical Score Featurette produced by RKO Radio (22:28) – This was made to promote the film’s original release in December 1945, and is played over the same film stills as the radio adaptations.

Theatrical Trailer (1:51) – A perfect way to compare the film against this trailer and see the amount of work that has gone into the restoration process.

Image Gallery – This is slideshow of 35 images. There are gorgeous chiaroscuro snaps, candids, as well as magazine covers, set images and colour posters.

First pressing only: Fully illustrated booklet containing new writing on the film by Ronald Bergen.

Reversible sleeve featuring original and newly commissioned artwork by Jennifer Dionisio.