In Two & Two (2011) – Babak Anvari’s BAFTA-nominated short allegorical film – a teacher (Bijan Daneshmand) attempts to re-educate his male pupils with some basic arithmetic, claiming that what they have always been taught is no longer true. The writer-director packs quite the punch with very little exposition and a whole lot of nuance when depicting the absurdity of an authoritarian regime/dictatorship. Which all bodes well when your next film – and first feature – is an effective little horror (and would become BAFTA award-winning in its own right). It is also a lovely touch to have that same actor play the University Dean who is responsible for shattering Shideh’s dreams of becoming a Doctor.

Under the Shadow is set in Tehran during the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s and Shideh (Narges Rashidi) can no longer study medicine having been removed for her political beliefs. We are never party to what exactly her transgression is but suffice to say with the mention of ‘radical left groups’ she was – and probably still is – against the war that is currently waging in her country.

Once her chador is removed, we can ‘see’ some of her transgressions. Her hair cut (in a bob style), dress (westernised), and her autonomy around her home; the partnership with her husband, exercising to Jane Fonda. she’s also the only woman in the building who drives. This is a ‘modern’ woman, oppressed by external tradition and reduced to the confines of her four walls, and even those are not so secure with the shelling, daily explosions and air raids which can send residents into a panic at any given moment.

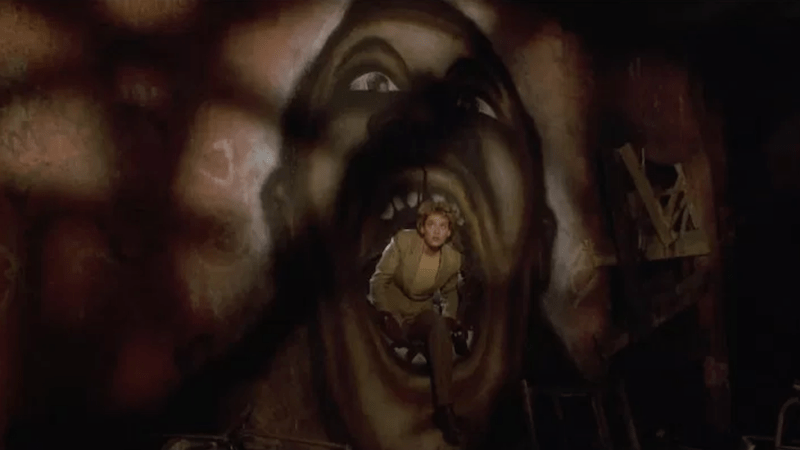

When her husband Iraj (Bobby Naderi) receives his draft notice, Shideh is left with her young daughter Dorsa (Avin Manshadi) as, one by one, all her neighbours pack up and move onto safety. The exacerbating factor a shell crashing through the roof of their building, killing the elderly resident within and leaving a gaping hole. The hole is covered with a sheet which appears to undulate in the wind like a bodily organ, flapping in and out like a heartbeat. A visual metaphor of a damaged culture, while the cracks in the ceiling – it can be argued – relate to Shideh’s psyche. Ever increasingly isolated, Shideh and Dorsa begin to experience things which may be the product of a child’s imagination or something altogether more supernatural.

Djinn is a malevolent spirit which has its history in Early Arabia and then later in Islamic mythology and theology. An entity that travels on the wind until it finds somebody to possess. Often dismissed as a superstitious belief, the spirit is reported to enjoy the souls of children (much like Krampus in European culture, or el Cuco in Latin America). It may explain Dorsa’s fever or not, after all Shideh was also once a child. Evil wants to hurt them alleges one neighbour while another, Mrs. Fakur (Soussan Farrokhnia), attempts to allay her friend’s fear: “people can convince themselves of anything if they want to”.

Tight framing adds to the oppressive atmosphere as mother and daughter’s fear and anxiety builds. Tension is slow-burning, and jump scares are few and far between yet effective when they do occur. There’s no score (music is only played during opening and closing credits) so is reliant upon diegetic noise and whistling winds. We’re never sure of the time of day given the constantly closed curtains and disturbed sleep patterns.

What appears to be mere moments gives the impression of hours. As people leave we can assume the passing of days and weeks yet the costumes of the leads mostly remain the same. Natural and artificial also play havoc with this, along with the production design: one location, open doors, hallways, and reflections in the television mean the constantly moving camera plays tricks with the eyes – was that something moving or not? Shideh’s lip is bruised from the constant biting, insecurity, anxiety, stress. Like all amazing genre films – nothing is ever quite how they appear and this film is all the better for it building beautifully the general sense of unease.

It seems apt that when she is preparing to fight, Shideh’s weapon of choice is a pair of scissors – as if tethered to a more domesticated past, her own mother’s apron strings or the chador in this instance. While the malevolent being appears to be set on persecution – even referring to the character as a ‘whore’ and ‘bad parent’ – it’s important to remember that Djinn is not inherently evil or good, and this entity could, at some point, be Shideh’s mother from beyond the grave.

A matriarch disappointed that her daughter will no longer practice medicine but needs to save her by forcing her to leave the building. Think back to the picture frame which houses Shideh’s mother’s portrait, the fractured glass obscuring the image within, it now laying down on the shelf hidden from view – but before that, the draped material serving as a backdrop in the photo is identical to the chador the entity embodies itself within. This reading further strengthens the mother-daughter links throughout, and the expectations a patriarchy levels at women, generally, but more so during the kind of regime in Tehran of the 80s.

As a first feature, Under the Shadow wears its influences well: Polanski’s apartment trilogy (Repulsion [1965], Rosemary’s Baby [1969], The Tenant [1976]) with a sprinkling of Hideo Nakata’s Dark Water via a domestic social realist drama in the ilk of Abbas Kiarostami and Asghar Farhadi. It’s a rich and visually arresting film which checks all of the above as well as featuring, at its heart, a really affecting horror fable. A 1980s Tehran-set horror film filmed entirely in Farsi – the first of its kind.

Finally, it has been given the kind of release it deserves courtesy of Second Sight that includes plenty of extra features, including five new interviews with the filmmaker, cast and crew, as well as a lively commentary between Director Anvari and film critic Jamie Graham, in which every aspect of the film’s genesis, production and release is covered.

Extras

Two & Two (8:48) – Babak Anvari’s BAFTA-nominated short film shown in its entirety. It’s the one extra which can be watched before the main feature.

Escaping the Shadow (23:53) – A long interview with Anvari who begins with his own childhood nightmares growing up in 80s Iran before his move to Britain. He talks at length about the filmmaking process, his cast, shooting in Jordan and expands upon things mentioned in the commentary. He’s a delightful interviewee, and while it is not the most imaginatively filmed featurette, Anvari’s charisma shines through.

Within the Shadow (12:52) – Star of Under the Shadow, Narges Rashidi discusses her own childhood in Iran and Germany and career now she is LA based. She describes the film as a ‘beautiful gift’, and again, static camera and a by-the-book interview reveals an excitable and rather lovely person.

Forming the Shadow (16:11) – Lucan Toh and Oliver Roskill talk all things ‘producer’, how they met Babak, the script, the film’s potential and their brief disappointment at not having to sell the film when it premiered at Sundance. A lot of their anecdotes are repeated in the commentary track.

Shaping the Shadow (13:29) – Anvari’s close collaborator and DoP Kit Fraser talks about his involvement from before the script was even written.

Limited Edition Contents – This set is limited to just 2000 copies, comes in a rigid slipcase featuring new artwork by Christopher Shy and with a soft cover book with new essays by Jon Tovison and Daniel Bird (unavailable at time of review). Plus behind-the-scenes photos, concept illustrations, and a poster with new artwork.