The Western can be described as an opportunistic film genre[1], one often utilised as an ideological tool to re-write American history, and Kevin Costner has taken the occasion to create a mediocre revisionist Western fable. A cinematically, epic journey which is, admirably, the actor’s debut in the forum of directing. Costner has clearly taken inspiration from auteur John Ford and this is evident in Dean Semler’s sweeping cinematography of the Western frontier and surrounding landscape. Dances with Wolves[2] was born from an age of political correctness and post-Vietnam sensibilities and can be read as an apology for Westward expansion.[3] This film appears to be about righting wrongs, idealising and romanticising East/West history.

Much like Ethan Edwards (John Wayne) in The Searchers[4] following the end of the Civil War, Lt. John Dunbar (Costner) is on a quest to discover or re-cover his identity. The war has left him disillusioned and in search of change whether that be physically, emotionally or geographically. While The Searchers (and many more besides) depicted American racism, Costner attempts to propagate the notion of good and evil in the culture of Red and White, often seen as antinomies[5] of the Western genre – here, Sioux/Pawnee tribe(s) and Dunbar/Union Comrades. Both races are ignorant of difference and fear is driven by an ignorance of the respective worlds in which they reside. Dunbar embraces the tribe and attempts to assimilate into their world, offering his ‘White Man’ wisdom in an exchange of ideas.

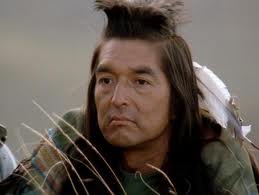

Michael Blake’s screenplay based upon his novel of the same name replaces the Comanche Indian with the Sioux tribe and each character performance delivers gravitas not least due to casting. White actors in ‘red face’ of the classical Hollywood era have, thankfully, been replaced with actors of Native American origin and defy stereotypes. Graham Greene, Rodney A. Grant, Wes Studi and Floyd ‘Red Crow’ Westerman depict the multi-faceted Native American and attempt to reconcile the ambivalence and ambiguity of the human spirit (something that the more-recently made Twilight Saga[6] has failed to do). They are, however, rarely shot alone within the frame and are often seen in groups; the ‘pack’ to Dunbar’s ‘lone wolf’. The same human ambiguity cannot be said for the female characters within the picture. There are two women who appear within the mise-en-scène, Black Shawl (Tantoo Cardinal) and the other, Stands with a Fist (Mary McDonnell). The latter is a white woman who has lived with the tribe since childhood and the only female who shares any prominence in the narrative – she is the means by which the two worlds of East and West/Civilisation and Wilderness can communicate effectively. When she is first introduced onscreen, she is in the same place of despair as Dunbar in the film’s opening shot; bloody, alone and without a reason to live.

It comes as little surprise that Dunbar, now named Dances with Wolves, marries Stands with a Fist and by doing do re-enforces the white patriarchal ideology of the American identity. He has been the man caught between two cultures and attempts to birth a new identity – here alluded to by the removal of facial hair and Military dress. He grows his hair, wears Native dress and speaks in Native tongue, yet by marrying the only white woman in the tribe, miscegenation is avoided and the white race can continue to dominant the screen. Dunbar fights shoulder-to-shoulder with ‘his’ tribe in another Civil War, this time Sioux against Pawnee. This is a war he agrees with as the purpose is to make men free and is not ruled by political objectives.

First-time director Costner spends a slow-paced 114 minutes attempting to reproduce a version of the American ancestor, one that descendants can be proud of. One of racial inclusion, of understanding and empathy and yet the exclusion and absence[7] of the African-American race during the time of slavery and Civil War speaks volumes. Although, the subsequent release of films like Django Unchained[8] highlights the role of the African-American cowboy in history – the last film of note to depict a black character in such a film was Unforgiven[9] – there seems to be little room for a multi-ethnic American identity as the pre-dominant patriarchal white ideology still takes precedent and the ‘Frontier Hero’ will always, it would be appear, be white.

[1] French, P. Westerns: Aspects of a Movie Genre, UK: Carnacet Press Ltd [1977] (2005).

[2] Dances With Wolves (1990, dir. Kevin Costner).

[3] Barrett, J. Shooting the Civil War: Cinema, History and American National Identity (London: IB Tauris 2009, p81).

[4] The Searchers (1956, dir. John Ford).

[5] Kitses, J. Horizons West, London: BFI (1969).

[6] The Twilight adaptations have replaced the word Indian with Wolf but still depict Native Americans as angry young men waging war on the ‘White’ (Vampire) man.

[7] Cripps, T. ‘The Absent Presence in American Civil War Films’ Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, vol.14, no.4 (1994) p.367

[8] Django Unchained (2012, dir. Quentin Tarantino).

[9] Unforgiven (1992, dir. Clint Eastwood).