There have been numerous attempts to depict the cruelty of dementia onscreen, detailing the disease, from diagnosis to decline. Often told from the (adult) children’s perspective, most of these films comment on the hardship and then the parent is often shoved into assisted living – despite refusal – where there are medical professionals who will help them. Viggo Mortensen’s Falling doesn’t necessarily reinvent the wheel, however, his film is a family drama first and foremost with dementia in a supporting role.

The actor was on a night-flight returning from his mother Grace’s funeral in 2015 when he initially got the idea for a film. At the wake, he noted in his journal all the conversations he’d had and overheard, a lot of which triggered remembrances from childhood. He was intrigued by the differing recollections of memories (often the same ones) shared during the memorial.

Memory is a theme which has recurred through his previously published work, including books Coincidence of Memory, and I Forget You for Ever and makes up the genesis of Falling, his feature debut as writer-director. This debut is seen through the eyes of John Peterson (played respectively Luca & Liam Crescitelli, Grady McKenzie, Etienne Kellici, William Healy and, finally, as an adult by Mortensen himself) and uses fictionalised aspects of the actor’s childhood .

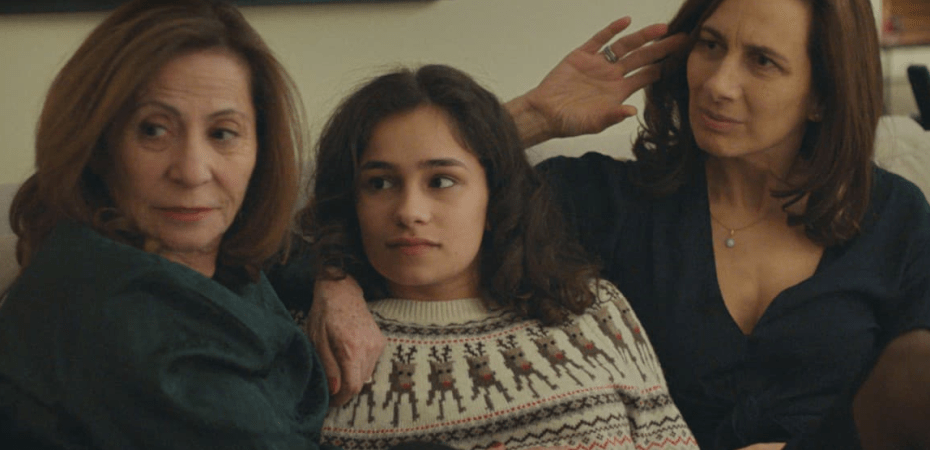

Willis (Lance Henriksen) is a belligerent old bastard of a man, foul-mouthed, abrasive and stuck in a time-warp. He is stoic and habitually unmoving in his attitude and views of the world, made all the more problematic by his advancing dementia. His son John, a pilot, who lives with his partner Eric (Terry Chen) and daughter Monica (Gabby Velis) in California brings Willis to visit so that he and sister Sarah (Laura Linney) can make plans for their father’s long-term health-care. Specifically, selling the farm in upstate New York and finding somewhere geographically closer to them so that they may share the care-load.

Willis’ reaction comes as no surprise to the whole idea. Cue a multitude of slurs, expletives and the testing of anyone’s patience but John remains calm, reticent and immune to the insults until, well, he isn’t. In a series of flashbacks, we see there is no love lost between father and son – the term “cocksucker” is used as both an expletive and term of endearment. It is these flashes of memory that give way to happier moments as Willis – the younger iteration played by Sverrir Gudnason – and Gwen’s (Hannah Gross) love story is detailed in snatches of scenes, like a slideshow, depicting their wedding day, the birth of their children and the inevitable fracture and breakdown of their relationship. These snapshots are interwoven with moments seen through the eyes of their children.

Amongst these, we see father and son bonding, hunting and fishing on the lake, the joy evident on the little lad’s face. There was affection once-upon-a-time but as John grows and away from Willis’ overbearing control, through divorce after divorce, the relationship becomes fractious building to a head during the boy’s teenage years.

The film frames Gwen as the love of Willis’ life, however, he doesn’t seem to know what true happiness is with or without her, and he spends the last few years of their relationship torturing her and trying to make her as miserable as possible. Yet, in a film which focusses on subjectivity and memory can the viewer take anything at face value or do we doubt everything? These flashes belong to multiple people, their perceptions as they experience them, and then there’s Willis’ recollections are even more questionable due to his advancing years and disease.

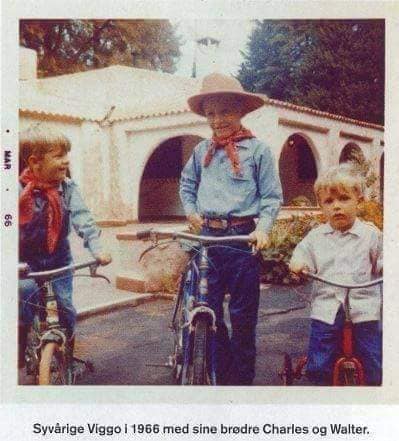

Mortensen comes across as a fairly unassuming and private man which makes this all the more fascinating. Reportedly working for free in order to finance this film, the film’s producer, director, screenwriter and composer chose to fictionalise some elements of his early life and childhood without losing verisimilitude leaving the viewer to question what the ‘factual’ element is. Apparently, Little Viggo (he was never know as junior) did have a dead duck as a pet which fed his ‘obsession’ with death, and the scar above his top lip was allegedly caused by barbed wire (and not by his father’s hand as the film suggests). He’s not a pilot either but his brother, Walter, had a cameo as one in an early Mortensen film, The Crew (1994). Their other brother Charles is also named in the film’s pre-credit dedication – there is no sister. In reality, Mortensen apparently took on the lion-share of caring for their parents – both of whom had dementia – prior to their respective deaths, Falling is not only a love letter to lost parents but for his younger siblings.

There are little nuggets of information scattered throughout that, upon first viewing, few would be aware of but serve as nods to the Mortensen/Atkinson family history. It is clearly no accident that John has the surname he does. While Mortensen went by Little Viggo, his father tended to be Peter. John Peterson is, symbiotically, Peter’s son. Much was made of Mortensen’s choice of sexuality for his main character, however, he has stated in interviews that he wanted to exaggerate the polarisation between father and son. Both are presented in a very specific microcosm of American society – you’d be hard pressed not to miss the Obama image on the fridge – and a Presidential term that was afflicted with the darker aspects of misogyny, racism, homophobia and misanthropy (it was to get oh so much worse with the 45th). Themes suggested in this narrative. John and Willis are at odds over political affiliations, life choices, sexuality, as well as their memories of Gwen.

As a side note, it’s a really astute observation that the older generation i.e. Sarah and John won’t call out Willis for his bullshit opinions but his older grandchildren will. Monica, on the other hand will often lapse into Spanish (presumably she is the personification of the Mortensen boys’ childhood in Latin America) – her mother tongue – but is his best friend. She’s the only one who will accept him for who he is. Coincidentally, an immigrant like herself.

Mortensen’s maternal grandfather (and one brother’s namesake) was Canadian and a medical doctor and two Canadians plays Doctors here. Close friend and collaborator David Cronenberg (as deadpan proctologist Dr. Klausner) and Hannah Gross’ actual father Paul plays Dr. Solvei. Mortensen own son, Henry, also makes an appearance as law enforcement officer Sgt. Saunders. So many father and son references and yet the real driving force of the narrative is the mother – she is the conscience running through the film and, as previously mentioned, only in her absence is her (somewhat romanticised) presence felt all the more, the subjective memories of her often the bone of contention between father and son. For John, his mother has gone, his memories are relegated to the past while Willis – due to his declining cognisance – has Gwen in the present despite having had a couple of wives since her. She is whom he recollects, imagines her in front of him, and continues to love during his sun-downing.

Thankfully, they are eventually able to accept each other’s version of events, something Mortensen also learnt in real life. He told Alec Baldwin during his podcast episode that this is aspect he personally finds so unconvincing about the so-called ‘dementia’ films; the need to depict people as bumbling and forgetful, with their carers gently revising their recollections, as this wasn’t his experience at all. “One thing you learn is not to correct them. It’s too late – don’t argue anymore… if they’re enjoying the memory, let it go.”

It is those types of scenes, as Falling edges towards its denouement, that are the most heart-breaking as the son moves back in with the old man (Canada doubling for Watertown, New York state) who, in his confused state, believes his ranch is under siege – despite having sold parts of it and promptly forgotten. In reality, Mortensen Sr. would lapse into Danish to converse, often slipping back to his own childhood while the actor would sleep in the next room with a baby monitor for company. Onscreen, Henriksen’s Willis mistakes John for his own father. John has dealt with his father, his diagnoses and outbursts with relative calm, diplomacy and resignation up to this point but to hear him raise his voice, see him rage – albeit briefly – exposes more of his humanity, pain and sorrow etched upon his (unshaven) face, and his usual perfectly coiffed hair standing on end.

It’s the first time his guard slips, his usual immaculate appearance refreshingly missing while Red River plays on a small portable TV in the background. In Howard Hawks’ 1948 Western things get tense between John Wayne as a Texas Rancher and his adopted son, Montgomery Clift. It’s no coincidence that John is trying to broker a deal to sell the remaining land given his ornery father is now too infirm to work it or save it. It also serves as a reminiscence back to a ‘simpler’ time, the old west in which ‘men were men’, a (toxic) masculinity which Willis clearly subscribed to but is also frozen in suspended in time, unwilling (unable?) to change. Décor of the surrounding rooms and even Mortensen’s costumes cement this, all are dated and somewhat old-fashioned. Henriksen’s performance is extraordinary throughout and especially in these moments, enabling such sympathy in a man who has up to that point been largely unpleasant and devoid of sentimentality is certainly no mean feat.

Falling is gorgeously edited by Ronald Sanders (A History of Violence, Eastern Promises, A Dangerous Method) and stunningly shot by DoP Marcel Zyskind (The Two Faces of January, The Dead Don’t Hurt). Certainly, it didn’t hinder the first-time director having a cast and crew of familiar people/frequent collaborators working alongside him in what proves, to be a beautiful and cathartic experience, one that stays with you. There is a lot to admire and be moved by.

It asks questions about age, memory, its perception, recollection, retainment and reconstruction – and its persistence (there’s even a sneaky nod to Dalí’s 1931 painting, see image above) the notion of verisimilitude, and, above all else, forgiveness. This is no typical screen dementia patient, there is no withering away quietly – here the patriarch keeps his personality, his faults hard to ignore. He is tenacious, angry, insecure, his presence overwhelming at times; impossible to love and loved anyway. It’s a film which reconciles life with the parent you have with the one you might have wished for, full of compassion, empathy, and grace.