There is nothing worse than losing sleep and there is a special place in hell for anybody who comes for it and your peace of mind. This is something that Nicky (Lyndsey Marshal) quickly learns after new neighbour “Deano” (Aston McAuley) arrives in writer-director Jed Hunt’s feature debut Restless.

In an unnamed coastal town, empty-nester Nicky works practically all week in an understaffed and underfunded social care facility. Her days are, admittedly, a little banal but she – like the rest of us – relies on the small joys when she can claim them: listening to the classical music her late father insisted upon at breakfast, cooking dinner, baking to Beethoven, reading a good book and settling in on the sofa unwinding to the televised dulcet tones of Ken Doherty on the snooker (the heart wants what it wants). She lives vicariously through her teen son Liam (Declan Adamson via telephone) who is away at university. She grimaces during their latest chat when he tells her he’s off out to see an original cut of The Exorcist. Little does she know, she’ll perform her own exorcism over the next seven days.

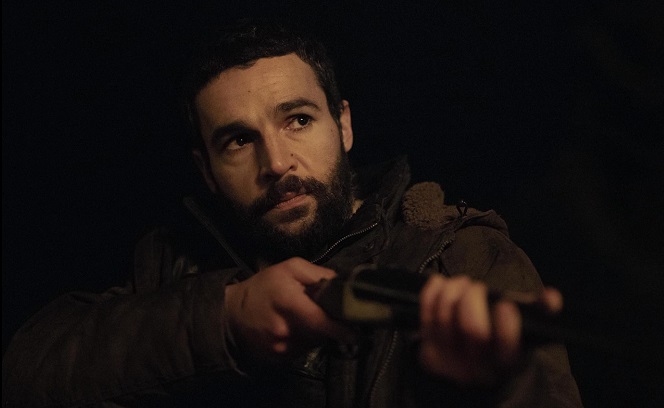

It starts out harmless enough, just a small group unpacking a car. A blur of tracksuits and a fierce looking dog. Then the music starts, the antithesis of Rachmaninov, Vivaldi, Tchaikovsky et al, pound-pound-pounding through the walls. At first, Nicky drives to the waters edge with a pillow and gets some shut-eye before a new day dawns, bumps into Keith (Barry Ward) who invites her out for a drink later in the week (presenting her with a violin because of her love of classical music but that’s another story). He’s as sweet as he is cringeworthy. When deafening dance music keeps her awake a second and third night, she knocks next door and politely asks that Deano turn it down and is met with faux-niceties and “I got yer.” By day five, all out war has been declared as vengeance is vehemently pursued.

The performances – led so ably by Marshal – save Restless from being just another bleak kitchen-sink style British drama, it is actually something else entirely disguised as such and manages to surprise and swerve expectation. Lazy writing could have had these characters teeter and plummet into stereotype territory but a decent script by Hunt manages to always remain believable. The subject matter will be heavy for some – there is plenty of sly commentary on the state of the care and class system in Post-Brexit Britain where the sense of community (unity especially lacking) is null and void in places – and plenty triggering if you have ever lived next door to antisocial idiots who have little respect for others.

There are some memorable moments, Kate Robbins is a particular standout as Jackie who loves a fight – we all know someone like her – the cinematic flourish of the dream sequence is brilliant and the soundscape is fascinating even if the visuals can be a little on the nose at times. Nicky’s loss of reality and descent into mania is relatable (especially for those of us who have had to share a wall with hellish next-door neighbours), tense, uncomfortable and humorous – when she bakes the “special” brownies for Dean, the level of self-satisfaction even smug expression she wears is hilarious.

That’s what makes this debut work the most, the humour, which is why one can forgive the ending. Not sure, the felineicide is really sufficiently punished (#JusticeForReg) but some levity is absolutely needed given how near the knuckle the “reality” at times feels. This is testament to Hunt’s taut script and direction, David Bird’s almost vérité-style camerawork, Anna Meller’s editing, Ines Adriana’s integral and superlative sound design, and as, previously mentioned, lead actor Marshal.

Her nuanced performance carries the film in its entirety and that isn’t to dismiss McAuley’s turn as Deano but often it’s waiting on Nicky’s reaction to him – or something inconsequential his late-night selfishness/shenanigans causes. They become two sides of the same stubbornly-headed coin and even start to dress in similar colours – which keeps the audience invested. Like when she leans against the kitchen sink hate-eating a crunchie™ or buying expensive headphones and trying meditation apps to lull herself to the land of nod. This brief look of resignation, fury or determination on her emotive face speaks volumes. The irony being that only through the enforced insomnia, is Nicky activated (so-to-speak) and finally fully awake.

Loathe thy neighbour indeed.