In the traditional Portuguese Tranny Fag translates as Bixa Travesty, a little less confrontational than the English but that’s just not the style of the documentary’s subject Linn da Quebrada – the self proclaimed “tranny fag”. Residing on the outskirts of São Paulo, she is marginalised economically before even considering the fact that she’s black and transgender, struggling to exist amid poverty and in a world that, for the most part, doesn’t comprehend her.

Rather than shy away from the public eye, Quebrada is taking the Brazilian funk scene by storm, alongside her partner-in-crime Jup do Bairro. Their songs – (performed throughout) providing a back story of sorts for the 27-year-old – contain abrasive coarse lyrics which pull no punches and berate society and the expectations it places on women, what it means to be a woman like her, and dismantling the patriarchy one bridge and chorus at a time. Her words are a weapon intent on holding the world accountable and paving a way of acceptance and understanding without inciting hatred.

As a subject, the singer-songwriter and spoken word artist is fascinating and inspiring. She’s pre-op and has yet to start hormones, consider breast implants or remove her facial hair because as far as she’s concerned she’d be pandering to society’s ideal of womanhood. Quebrada – who also co-wrote the script with directors Claudia Priscilla and Kiko Goifman – is a “black fag doll. Neither man or woman” embraces nudity, here and in her stage shows as an attempt to undermine, even recondition the collective mindset associating gender with genitalia and highlighting the façade of gender performance.

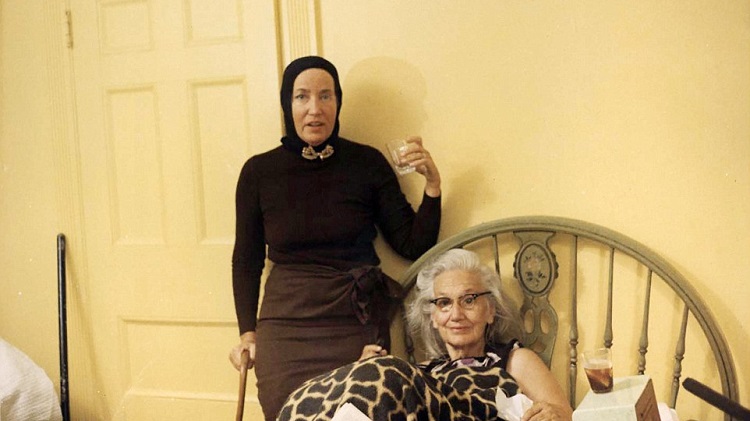

A real turning point in the documentary which jumps from talking head to music gig almost exclusively is the footage made during Quebrada’s treatment for testicular cancer, the physical effects and the profundity it had on the way she controlled her body. The scene which shows her literally pulling the lustrous locks of hair from her head, chemotherapy having ravaged her immune system is particularly powerful and in keeping with her persona, completely transgressive. This and the scenes with her mother offer a rare intimacy which is needed in an otherwise repetitive and prosaic documentary. The static camera and simplistic editing coupled with the pulsating combative stage performances start to feel isolating.

Tranny Fag is a LGBTQIA+ positive, important and transgressive, if slight, profile of a bold and beautiful artist who is unapologetically her confident self. She espouses her ideas and beliefs provocatively, is always interesting, and determined to not only stand out but belong in an accepting world.