Dramatic strains of Vivaldi strings play over the mini-bus crawling along as a tour guide announces to his passengers that they have arrived at their destination. Out everyone pours around the van to view whatever it is they have clearly paid to see, “so exciting, once you see the witches.” The what now? The camera captures what can only be described as a human zoo; behind metal barriers sits a group a women, dressed in blue, partially painted in white, their clownish make-up made more apparent as they howl and pull faces for the benefit of their visitors.

Shula (Maggie Mulubwa) – though she has no name until much later on – is an orphan who’s accused of witchcraft. Evidence is patchy at best, she has the ability to ‘curse’ water, make people trip and fall, and hack off a man’s arm (it miraculously grew back). The fact that she refuses to confirm or deny the charge means she is “cunning and deceiving” and before she knows it, she’s shipped off to government worker Mr. Banda (Henry B. J. Phiri) who oversees the small witch camp as seen as the start of the film.

After consulting a witch doctor who “proves” witchcraft, the little girl is fitted with a spindle and spool of white ribbon, the length of which varies from woman to woman, all to “prevent them flying away”. Shula is then offered the choice of either accepting her label and joining the women or cutting the ribbon and being transformed into a goat. It’s not difficult to realise which she will choose, she’s eight.

While the rest of the colony work tending the fields and hoping for rain, Shula is “witchified” and dressed in a frilly sack, twigs and leaves in her hair, white make-up adorns her face as she taken from village to village condemning thieves i.e. choosing the one she thinks is guilty. It’s ridiculous. The rewards she earns she shares amongst the women and that’s what is so bittersweet, there’s genuine camaraderie and affection between them and Shula now has a family, full of grandmothers – as all of these women are considerably older – sorrow, time and circumstance etched into their lived-in faces.

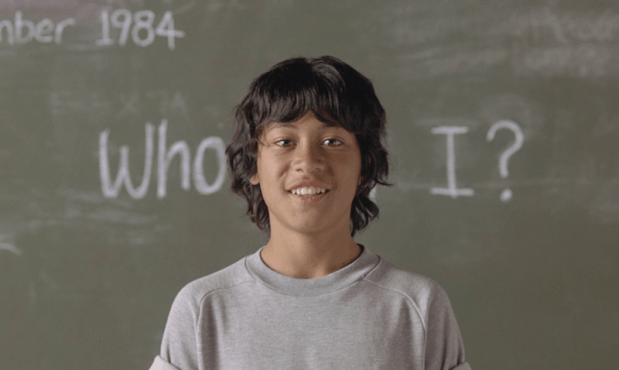

What strikes most about Rungano Nyoni’s first feature is how strong and self-assured it is. I Am Not a Witch is completely unique and striking in its gendered social critique and satirical rendering of persecuting patriarchal control. Thankfully, the comedy does not overwhelm but punctuates perfectly. The central performance which is mostly a silent one, by Maggie Mulubwa is rendered beautifully, her largely impassive and gorgeous face is often shot in close-up and the slightest expression is subtly mesmerising. The use of colour, which tends to be the odd swatch whether white, blue, red, purple, or the bright orange of the transporting truck is set against the dusty greys, and dirty sepia tones of the earth superbly. The impossible point-of-view shots, long languid takes, and narrative ellipses provide a visual erudition and subtle sophistication to the magical realism and that final shot is absolutely breathtaking.

I Am Not a Witch is a stunning debut, an amusing if poignant fable critiquing a very real social problem and making the Zambian-born Nyoni a filmmaker to watch out for in the future.