It was at the 90th Academy Awards when Frances McDormand took to the stage and declared to the seated guests, industry and world at large that women have stories to tell. One such fascinating tale belongs to Ms. Hedy Lamarr.

Alexandra Dean’s Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story begins with a quote attributed to the actress: “Any girl can look glamorous, all she has to do is stand still and look stupid.” Hedy was very glamorous but far from stupid. Her beauty allegedly transforming her from an ugly duckling in youth to become the very thing she was judged solely upon. Born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in Vienna, ‘Hedy’ was afforded private schooling (she particularly enjoyed chemistry) and exposed to the arts from an early age. By her own admission, she was an “enfant terrible” posing nude at 16 before developing an interest in acting. Which led to Ecstasy (1933) – a Czech film that saw her skinny dip, cavort naked lakeside and feign orgasm (the film’s rarely discussed outside of these “scandalous” moments). The Pope and Hitler denounced it, the latter not for its explicitness but rather the religious beliefs of its lead actress (the Kieslers were Jewish) – before Hedy set sail for Hollywood (she would become Lamarr courtesy of Louis B. Mayer’s wife Margaret) from London after escaping her first husband. There were six marriages in all, none particularly happy yet two resulted in children with motherhood a role she appeared to mostly enjoy.

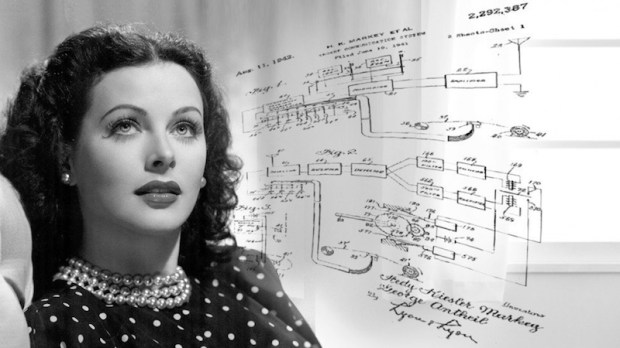

It was, however, her relationships with Howard Hughes and the composer George Entheil which would help sustain her love of invention (Hughes gave her access to his chemists and lab) and provide her with what Google animator Jennifer Hom, describes as a “perfect underdog crime-fighter-by-night-story.” Hedy would work all day and then, of an evening, experiment and in 1941 with Entheil, the self-proclaimed “bad boy of music”, she created a radio controlled torpedo, the 1942 patent of which could (and did, come The Cuban Missile Crisis) revolutionise the war effort. Instead, they were thanked for their time and Lamarr was directed to selling war bonds – she made $343 million’s worth. When MGM failed to provide suitable film roles she found them herself, producing The Strange Woman in 1946 and co-producing Dishonoured Lady a year later, a feat relatively unheard of, in Hollywood, outside of Dorothy Arzner and Ida Lupino.

Life was never plain sailing, there were more divorces, a nervous breakdown, the addictive ‘vitamin B’ shots from Dr. Feelgood Max Jacobsen, odd bouts of kleptomania, the botched cosmetic surgeries, the dubious autobiography and subsequent court case that she would lose costing around the $9.8 million mark, and her reclusion from the world. The lynchpin to all of this heartache, one could argue, is that patent, which today is worth $30 billion and is a technology used in wifi, bluetooth, mobile telephones, GPS and the military, and one which has effected our daily lives, and for which she was paid nothing. There was, at least, the Electronic Frontier Foundation Special Pioneer Award in 1997 and the eventual induction into the Invention Hall of Fame in 2014 (commemorating her 100th birthday) which would slowly inform the world of this genius woman who was more than just a pretty face.

In terms of documentary form, Dean’s approach is rather prosaic. From its piano-accompanied montages to the mixing of images, film clips, archival interview footage and talking-heads. These include Lamarr’s son Anthony Loder, daughter Denise Hedwig Colton, granddaughters, and a whole host of critics, biographers, historians – actress Diane Kruger also reads from personal letters. The crux of the whole film, however, rests on the lost and found audio tapes of an interview conducted in 1990 by Forbes Magazine staff writer Fleming Meeks. Hedy Lamarr gets to tell her own story and comes across as spirited and unpretentious with a wicked sense of humour; a fighter, survivor and a woman of extremes and complexity, which makes it all the more tragic that she became a media punchline and, in her later years, perhaps defined her self-worth against her ageing physical beauty.

Bombshell is an evident labour of love, passionately told (rarely sugar-coated), beautifully edited, by Dean, Penelope Falk and Lindy Jankura, and surprisingly moving. Its content and form, however conventional, is in much the same vein as Ingrid Bergman: In Her Own Words (2015) and even the more playful Mansfield 66/67 (2017); documentaries which seek to expose the myths of these successful women, subvert assumption and conflate the notion of brains and beauty (it’s amazing, a woman can have both in spades). Hedy Lamarr was an immigrant, a feminist icon – long before the term was coined – and a trailblazer in science and technology invention; an underestimated woman who, with her beautiful brain and frequency hopping, had a hand in literally connecting us all.