The power of fairy tales and stories in childhood can impact a lifetime not least due to the bedtime story whereby the adult attempts to lull the child to sleep with tales of wonder, and aid in the creation of dreams. Dreams, according to Freud, unconsciously assist with the resolution of a conflict and will be considered later, in greater detail, through an analysis of The City of Lost Children (1995). However, it is the action itself of storytelling which is intriguing, specifically between the adult, the child and the space they commune or what Maria Tatar refers to as a “contact zone”[1], a place of mutual meeting and experience as depicted in a film like The Fall (2006).

By distinguishing between the adult and child Tatar creates ambivalence, how can these two individuals share a mutual experience when she herself sets them apart from each other? Not to mention their individual reader identification and expectation[2]. The contact zone can be said to exist but it is not more likely a mutual meeting of contradictory experience (or even be described as repellent)? A story’s narrative sets both adult and child onto different paths. Adam Gopnik suggests that “the grown up wants a comforting image of childhood”[3] and is driven by nostalgia while the child uses the tales to move beyond childish things, a way of bypassing childhood and venturing out, albeit figuratively, into the world. There is even a suggestion that this contact zone/story space may extend to the dream-world specifically when considering Jeunet & Caro’s The City of Lost Children.

Fairy tales have, over the years, been the cause of much debate. Psychoanalyst Bruno Bettelheim stated that the tales speak directly to children[4] while Danish Folklorist Bengt Holbek maintained that fairy tales were written for an adult audience with children occasionally listening to narratives not meant for their ears[5]. What if they were written with both in mind? After all children are small(er) adults and adults are grown up children. Why should the listener or audience miss out on revisiting an aspect of childhood by vacating the realm of youth? It is the intention of this article to examine two original screen fairy tales in relation to the dual protagonists depicted, the notion of storytelling and the distinction of the ambivalent “contact zone”. The use of this concept, has been renamed the “story space” and may be a basis for the adult/child casting, however, this doubling or duality of character representation offers other possibilities, some of which will be explored.

In Tarsem Singh’s The Fall the protagonists consist of an adult and a child, strangers brought together by accidental circumstances. The film opens with an intertitle: “Los Angeles, long long ago” and scenes from the opening sequence quickly establish the setting in circa. 1915 California. Stuntman Roy Walker (Lee Pace) is languishing on the male ward of a picturesque hospital, confined to his bed after a stunt fall ends badly. Walker is a broken man in more ways than one, he has, not only, lost the use of his legs but the love of his life to the film’s leading man. Romanian immigrant Alexandria (Catinca Untaru) is on the other side of the compound in the children’s ward, her left arm in plaster following her fall from the top of a fruit picking ladder. Neither is necessarily destined to meet but both are isolated with few visitors. One day the wind blows Alexandria’s note to Sister Evelyn (Justine Waddell) out of her hands, into an open window and onto Roy’s lap.

So begins two exposition stories, one weighted in reality the other in an alternative world where the outcome is dependent upon how the real infiltrates the imaginary. Roy’s epic tale is a story of six unlikely companions; buccaneer and explosives expert Luigi (Robin Smith), ex-slave Otta Benga (Marcus Wesley), Charles Darwin (Leo Bill), The Indian (Jeetu Verma), a Mystic (Julian Bleach) and The Blue Bandit (Emil Hostina) and follows their quest to defeat the evil Governor Odious (Daniel Caltagirone).

So begins two exposition stories, one weighted in reality the other in an alternative world where the outcome is dependent upon how the real infiltrates the imaginary. Roy’s epic tale is a story of six unlikely companions; buccaneer and explosives expert Luigi (Robin Smith), ex-slave Otta Benga (Marcus Wesley), Charles Darwin (Leo Bill), The Indian (Jeetu Verma), a Mystic (Julian Bleach) and The Blue Bandit (Emil Hostina) and follows their quest to defeat the evil Governor Odious (Daniel Caltagirone).

From the start there is an indication that the visuals are formed through Alexandria’s imagination, elements within the fantastical realm are linked to the sights she sees around the hospital. She is providing the pictures while Roy creates the words. For example, much like The Wizard of Oz (1939), characters are drawn from the real world and find their way into the imaginary, Otta Benga is played by the man who delivers ice to the hospital and Odious’ henchman are costumed to closely resemble the Radiographer Alexandria is afraid of. Often the images and description do not correspond with each other, and the Indian of Alexandria’s mind is a man from India who wears a turban and who is mourning the death of his wife while Roy’s, unreliable, narration describes the man living in a wigwam and marrying a squaw[6].

The inclusion of the villainous Odious in the form of Sinclair (Caltagirone) the actor who has stolen the heart of Roy’s actress girlfriend once again confuses the narrative and thus the cinematic narrator[7] has to take over. It is also following this first segment of story that the audience is aware of the real reason behind Roy’s affection of Alexandria’s company. He is using the story space to manipulate the small girl and will only continue the tale after she has located a bottle of morphine for him so he can finally “sleep”.

Alexandria is dark-haired and adorably plump and when she is first shot, she is framed within a doorframe, a crucifix mounted on the wall above her thus suggesting that she is inextricably linked with the divine. She has a special relationship with the hospital’s priest and even steals the Eucharist from the chapel and shares it with Roy who asks her if she is trying to save his soul. Her green eyes, missing teeth[8] and stilted English make for an engaging and naturalised performance not least because the audience can occasionally miss snatches of dialogue. Her left arm is perpetually outstretched away from her body for the majority of the film’s runtime and she is almost always dressed in a white nightgown and taupe cardigan which she cannot wear properly due to the frame of the plaster cast. The wooden box she carries, which looks like a book, contains items she “likes”, photographs of her family, a spoon, small toys; a nostalgia box of memories.

Roy is also a brunette and despite their gender difference they are often clothed the same and often mimic each other’s body language (see images below). This may be an attempt by the adult to place the child at ease or perhaps is the visual depiction of the contact zone / story space previously discussed. Roy and Alexandria’s mutual experience of a fall, hospitalisation and subsequent isolation is the meeting place for them both. The story they both appear to enjoy, whether Roy wishes to return to his childhood or Alexandria wants to surpass hers, as Gopnik ascertains, remains to be seen.

On the surface, it can be argued that the girl represents the child Roy may never have. He has lost the love of life and the severity of his injury is never fully explored. For Alexandria, he may be a replacement father-figure having lost her father in a house fire. These are easy summations to make, however, another reading may suggest that Alexandria is Roy’s repressed inner child, or as described in Jungian theory, the Divine Child[9] who has manifested through his suicidal despair. This archetype, according to Jung, is weak by design, under developed but one which can bring happiness and instil hope when it has been lost.

While this, in part, is true, Alexandria is stronger and more mature, even at six, than the infant images which are associated with the Divine Child. She is just as manipulative as Roy and changes the narrative at will, even inserting herself into the story when it looks like the original narrator is close to death. Rather than embodying the child archetype she can be read as Roy’s shadow, quite literally becoming his double once she is a part of the narrative and injects herself into the imaginary world, referring to herself as the Bandit’s daughter, stronger than ever, with two perfectly formed front teeth.

In reality, the roles have reversed in the sense that it is Roy who is now visiting a prostrate Alexandria. She has made a second attempt at getting the bottle of morphine pills, broken into the dispensary and fallen again which has resulted in a serious head injury and Roy is visibly distraught at what he has caused. It is worth noting that after her fall, Alexandria’s recovery is seen through a series of cinematic stills whereby her back-story is shown through live action images and animatronics. Her life literally flashes before her and this sequence is much darker than Roy’s beautifully invented panorama suggesting a real ambivalence between experience and innocence.

Roy admits that the story was a subterfuge to push the girl into assisting his suicide but Alexandria stubbornly refuses to believe this, even after Roy begins murdering the tale’s protagonists one by one. She begs him to stop and he tells her that it is his story, to which she answers “mine too”. Roy, who was also inserted into the fantasy after the death of the Blue Bandit and is now personifying the vengeful Black Bandit, allows Odious to drown him while his double-in-miniature looks on. Back in the hospital, both Alexandria and Roy are in tears and she begs him “Please. Don’t kill him I don’t want him to die. She loves him”.

Alexandria then makes an admission, she has known all along what Roy intended to do with the morphine pills “I don’t want you to die”. In preventing Alexandria’s despair, Roy has to save himself and in the fairy tale world he bursts through the water, re-born, and saved by his blessing in disguise[16]. This confirmation of mortality, as experienced through Alexandria, is further explained by Bettelheim “[the] psychosocial crises of growing up are imaginatively embroidered and symbolically represented in fairy tales […] but the essential humanity of the hero, despite his strange experiences, is affirmed by the reminder that he will have to die like the rest of us”[10].

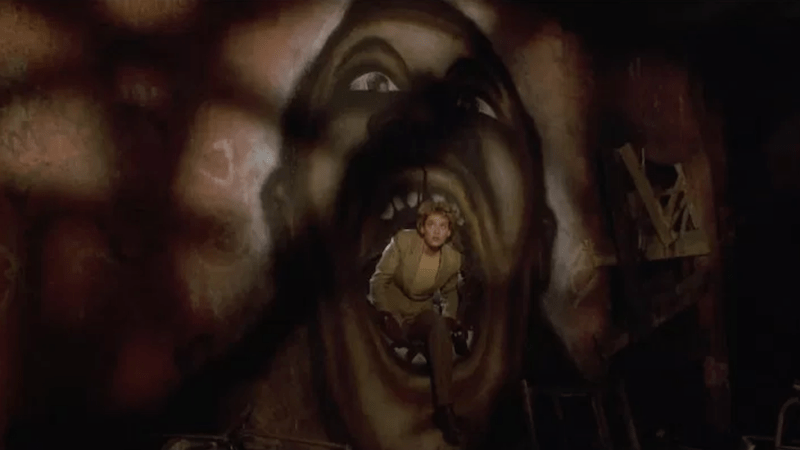

In The City of Lost Children, one character who is in denial about death is Krank (Daniel Emilfork). He is ageing at a progressive rate because he cannot dream; a lack of imagination is slowly killing him and so, he kidnaps children against the backdrop of a timeless, surrealist, Paris in order to extract their dreams and manipulate them as his own. He does this without realising that in his company they too cannot dream only produce nightmares which terrorise the thief in slumber.

Visually this text is very different from The Fall, where there was a palette abundant in colours and light, here there is limited light and the dominant colours are (as in Jeunet’s later film Amélie [2001]) red and green. This lack of light is metaphorical of the disorientating struggle displayed in the mise-en-scéne; this is a place where babies are left out in rubbish bins and not missed. Krank’s “uncle” Irvin is a disembodied brain which survives in a tank and in the opening twenty minutes serves as the intradiegetic narrator and sets the scene:

“Once upon a time, there lived an inventor with a gift for giving life. […] Having neither wife nor child, he decided to make them himself. His wife’s gift was to be the most beautiful princess in the world. Alas a bad fairy gene cast a spell on the inventor so that when the princess was born, she was only three inches tall. He cloned six children in his own image, so similar you could hardly tell them apart but the bad spell meant that they all had the sleeping sickness. He needed a confidant, so, inside a fish tank, he grew a brain that had many migraines. Finally, he created his masterpiece, a man more intelligent than the most intelligent men. Alas, the inventor also gave him a flaw. He couldn’t dream […] it made him so unhappy that he grew old unimaginably fast [and then] died in dreadful agony, having never had a single dream.”

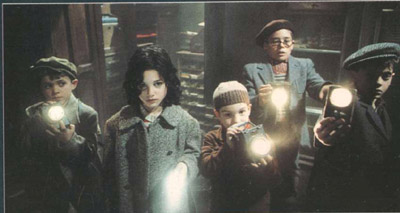

This is hardly the ideological filmic representation of hopes, wishes and desires that Jack Zipes describes when he is discussing the screen fairy tale[11] but a social commentary on the complex use of technology versus religious fundamentalism. The inventor creates his family through technology and essentially ‘plays God’ only to be worshipped by a cult of Cyclops who, in return for their sight, kidnap the children Krank requires for his dream-catching. The messianic figure of One (Ron Perlman) whose back story is linked with other fairy tales (Jonah and the Whale and Pinocchio[12]) enlists the help of an alluded-to Wendy[13], Miette (Judith Vittet) and her gang of Lost Boys/ urchins to rescue One’s little brother Denrée (Joseph Lucien). Miette and her fellow orphans work for The Octopus (Geneviève Brunet and Odile Mallet) identical twin sisters who dress, function, speak and work as one entity, conjoined at the leg.

While these dual characters are literally mirrored in their representation there are other characters which are connected subconsciously. Krank is beyond childhood without having actually experienced one and yet acts like a child, prone to tantrums and crying fits. Miette, on the other hand, is still physically in childhood but has the demeanour of an adult. Her orphaned abandonment has enabled her to mature quickly and her instinct for survival has her resorting to any means necessary to live, she is wise and tough far beyond her years. Miette and Krank are, in essence, two facets of the same person.

As described by Gopnik in his 1996 New Yorker article, Krank wants a way back into childhood while Miette wishes to embrace adulthood, even envisioning a relationship with the man-child strongman, One. When Miette and Krank come together in their contact zone/story space it is not through traditional storytelling but a dream in which they get to embrace their shadow selves and share a mutual experience.

Jung articulated this exchange in this way, “beneath the social mask we wear every day we have a hidden shadow side, an impulsive, wounded, sad or isolated part that we generally try to ignore. The Shadow can be a source of emotional richness and vitality, and acknowledging it can be a pathway to healing and an authentic life. We meet our dark side, accept it for what it is and we learn to use its powerful energies in productive ways […] By acknowledging and embracing The Shadow as deeper level of consciousness and imagination can be experienced.” [14]

Krank is dispossessed of a soul, an imagination and empathy and upon sharing consciousness with Miette – the girl who does not dream – can finally experience what he has been missing. In the same token, Miette can embrace her youth and rescue the man she loves. The child in the crib is dressed in pyjamas which are the same colour and style and the boy’s hair has been reddened, he resembles a young One, this is evidently how she reconciles the contact zone.

Interestingly, only when the child starts to morph into Krank does the ageing process begin, the Shadow selves meet. Unlike The Fall, where assumptions are made regarding Alexandria and Roy’s future selves, here Krank accepts his Shadow and so begins his regression. In opposition, Miette begins to wither and age until the demented dream-catcher is a baby. Miette must embrace her biggest fear so she can move forward and that is imagining One dead. This interchange of dreams kills Krank in reality thus substantiating the importance of imagination, use of enchantment and originality.

Fairy tales give the adult reader a re-presented imagination. Understandably, the physical child may have evolved but these screen tales enable the repressed child to re-emerge through viewer identification. Perhaps, just like the children in these texts they enforce a sense of hope, strength and resilience which has long been forgotten.

The inclusion of a child within an adult diegesis serves more than just viewer manipulation[15]. This division of realities and mirroring of locations, narratives and characterisations is an integral part of the postmodern film and more specifically this dual nature is present in screen fairy tales. While the texts that have been considered here have a very distinct separation between the real and imaginary, it would be worth considering the screen fairy tale which is based in reality and consider what purpose they may serve for an adult audience.

Sources

[1] Maria Tatar, Enchanted Hunters: The Power of Stories in Childhood (New York/London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2009). A term borrowed from Mary Louise Pratt. Tatar changes the context of the original contact zone and sets about making her own.

[2] Ibid. p242. “The power of reading together derives in part from the fact that it involves a transaction between more than a single reader and a text. The dialogue that takes place between the [storytelling] partners fuels the transformative power of the story, leaving both the child and adult altered in ways they might never have imagined. [Mary Louise] Pratt found in contact zones a process of transculturation, with colonizer and colonized entering into lively, two-way cultural exchanges”.

[3] Adam Gopnik, “Grim Fairy Tales”, The New Yorker (November 18, 1996) p96. http://www.newyorker.com/archive/1996/11/18/1996_11_18_096_TNY_CARDS_000376397 [accessed 10 January 2012].

[4] Bruno Bettelheim, The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales, (UK: Penguin, 1991).

[5] Bengt Holbek, Interpretation of Fairy Tales: Danish Folklore – A European Perspective, (Denmark: Suomalainen tiedeakatemia, 1987).

[6] These differences can also be examples of Pratt’s ‘contact zone’ specifically with the cross-cultural experience between American Roy and Romanian Alexandria.

[7] Seymour Chatman, Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film, (USA: Cornell University Press, 1980).

[8] Missing teeth as a motif are used throughout the picture. Roy tells Alexandria that power is symbolically associated with teeth and that she is currently “missing some strength”. Upon further investigation, however, teeth can be associated with illness and death and even a lack of faith (Greek) and in Chinese culture missing teeth symbolise telling lies. Some cultures believe that losing teeth can be sign that an individual has placed more faith in the word of man and has lost trust in God.

[9] Carl G. Jung, Essays on a Science of Mythology: The Myth of the Divine Child and the Mysteries of Eleusis, (USA: Princeton University Press, 1969).

[10] The movie’s tagline is quite apt here. Only at Roy’s lowest ebb did she manifest.

[11] Bettelheim, 1978 pp39-40.

[12] Jack Zipes, Happily Ever After: Children and the Culture Industry, (New York/London: Routledge, 1997) p9.

[13] One is an ex-whaler and following the loss of this job is hired by a travelling circus, of sorts, as a strongman. Aside from size he is for all intents and purposes a boy.

[14] J M Barrie, Peter Pan, (UK: Puffin [Re-issue], 2014).

[15] Jung, cited in Connie Zweig and Steve Wolf, Romancing the Shadow: A Guide to Soul Work for a Vital Life, (UK/USA: Random House Publishing 1999) p21.

[16] Karen Lury, The Child in Film: Tears, Fears and Fairy Tales (UK: I B Tauris & Co Ltd, 2010). Lury likens the child to a pet and even refers to both as ‘it’, she ascertains that the inclusion of children within a narrative is merely to serve an emotional purpose for the viewer.