Theodosia Goodman was the eldest of three children born to a Polish father and Swiss mother in Cincinnati. The Goodmans lived in the leafy suburb of Avondale until 1905 when their daughter left for New York to become Theda Bara. The name an anagram of “Arab Death”[1], made Bara the epitome of exotic temptress known as the Vamp. She, at the time, allegedly used her sex appeal to manipulate and embodied voluptuous transgression – the exact attributes that Post-Code Hollywood attempted to make commodity and control. In total, Theda Bara made over forty films between 1914-1919 including Carmen[2], Cleopatra[3] and Salome[4], yet it was her first leading role which cemented her as The Vampire. I propose that it was this dichotomous ambivalence and marginalisation in both characters portrayed and persona[5] which started a promising film career but essentially the ideology could not last and ended it too soon. Taking inspiration from a Philip Burne-Jones painting and Rudyard Kipling poem in 1897, A Fool There Was[6] intercuts verses of Kipling’s poem with scenes which are, it would seem, an introduction to the lead characters. An iris reveals a male, who is later revealed to be Mr John Schuyler (Edward José), shot, sat behind a desk gazing at long stem roses, he looks directly into the camera before picking up the flowers and smelling them. After the second verse of the poem, The Vampire (Bara) stands haughtily next to a vase holding similar flowers and picks one out, smells it and then pulls the bud from its stem crushing the delicate petals between her palm. She is dressed in heavy, dark materials and fur, jewellery adorns every other finger perhaps symbolising living beyond her means, or as Molly Haskell describes them “emblems of her wickedness”.[7] The silent film is set within the melodramatic mode consisting of two dominant styles, as identified, by Roberta Pearson, “the histrionic and the verisimilar”[8]

John Schuyler and his family are white, in not only skin tone but within the mise-en-scène. His wife, Kate (Mabel Fremyear), daughter (Runa Hodges) and sister-in-law (May Allison) are nearly always shot outdoors in natural light and dressed head-to-toe in white costumes. The Schuyler’s daughter, who later is referred to as ‘innocence’, is fair-haired, her blonde ringlets bouncing as she runs. She is, physically, a Mary Pickford/Lillian Gish in miniature, perhaps an indicator of the next generation which will resemble America’s Sweethearts[9] and not the dark, mysterious threat of the Vamp. A dialogue intertitle introduces The Vampire (Bara) so called because she has the sexual prowess and potential occult ability to drain their life source and wealth. The uncanny is aligned with this predator to enhance her otherness in relation to the ‘norm’ – the white, faithful wife and as Sumiko Higashi writes, “implied that her powers were supernatural or that she was, at the very least, inhuman”[10] She is dressed almost exclusively in black, hypnotically so, with an occasional white accessory, as if she were trying to assimilate into “decent” society. The Vampire reads of Schuyler’s trip and Statesman honour while resting at home. She has a black housemaid and an Asian male in attendance and this simultaneously whitens her against their ethnic variations but in the same token reminds the audience that she herself is ‘othered’ when considered alongside the Schuyler family.

As she boards the ship two previous victims (as they are described in the intertitle text) attempt to get her attention; one is a tramp who gets lead away by a police officer, the other, Mr Benoit, pulls out a gun and threatens to shoot her. The Vampire merely laughs and knocks it away with a flower and coaxes Benoit to commit suicide offering him one last kiss; “kiss me, my fool” before he pulls the trigger at his temple. His death fails to move her and she is reported, by the ship’s porter, to have stood over his body “laughing like a she-devil”. When Schuyler first sees this woman she is framed by a porthole powdering her nose which suggests a subtle hint at female consumerism. She has one eye on her own reflection and the other on her “prey”.

Visible through this porthole and clearly comfortable on deck, The Vampire can be read as a symbol of xenophobic (American) fears of immigration. Numbers of immigrants increased dramatically during the years 1899-1910 and while there is an attempt to Americanise The Vampire. Full assimilation fails as her ethnic femininity and,

[the] vamp persona [situates] her at the intersection of two established representative tropes: the predatory female vampire and the immigrant whose assimilation skills and potential for economic and cultural contribution were uncertain[11]

As an ethnic ambivalent, The Vampire may well have been the all-desiring temptress, however, to describe her as the representation of “the [unleashed] male sexual instinct”[12] as Higashi does seem a little extreme. She and, in this instance, his wife personify the polar opposites constructed through Patriarchy with the wife and child further representing social and moral order, and The Vampire revelling in the destruction and exploitative chaos her ability to emasculate exacerbates. In a Post-Code Hollywood future, as the femme fatale[13], she would be contained, however, Pre-Code, in these early films she was a player in the “fallen man genre”[14]

Even when society turns its back on Schuyler, his mistress brazens it out and walks with her head held high. She, much like the name she is given, sucks the wealth and life from her victim gaining more audacity and strength from his, increasingly, alcohol-induced catatonic state. Schuyler’s gait, once upright begins to stoop and his hair whitens: “The Fool was stripped to his foolish hide”. While this representation of woman displays a level of sexual freedom and independence, it can be limiting to female actors merely providing another stereotype to play in a male world. Theda Bara’s enigma was open to many an interpretation was described by James Card in the following way:

Endless lure of pomegranate lips…red enemy of man…the sombre brooding beauty of a thousand Egyptian nights…black-browed and starry-eyed…infinite mystery in their smouldering depths, never to be revealed…Mona Lisa…Cleopatra…child of the Russian countryside…daughter of the new world…peasant…goddess…eternal woman[15]

Her persona was created and cinematically, as The Vamp, was seen to promote a cultural threat; that of female immigrant sexuality and as Diane Negra writes “was an ideal figure to manage cultural anxiety” and reflected a real need to regulate female sexuality (and the growing birth rate).[16] Bara seemed to be at odds with the direction her film career was taking and tried, somewhat unsuccessfully, to diversify the roles she signed up to, including Romeo and Juliet[17]. The virginal Juliet was an unlikely role for The Vamp archetype and some reviews were critical of her acting style. Like most of her contemporaries, Bara was a student of the Delsarte method. François Delsarte (1811-1871) was the founder of an applied aesthetics system which included rhythmic movement, kinesics and semiology.[18] This system would have given film audiences pause for thought as every emotion was rendered through an eye or bodily movement.

The real reasons why Theda Bara’s career failed at longevity are unanswerable. The Vamp and émigré artist still continued to make pictures, names like Naldi, Negri, Valentino, and eventually Garbo and Dietrich cemented their places as household names. Bara appeared to grow tired of the limitations that The Vamp construction placed on the film roles she was offered and often this would be evident in some of the newspaper and magazine interviews that she gave. She made a last short, comedic film in 1926 called Madame Mystery which was co-directed by Richard Wallace and Stan Laurel but then seemingly retired after marrying. Bara died on 7 April 1955, aged sixty-nine from abdominal cancer leaving behind a lasting cinematic legacy as the original screen Vamp.

Watch one the few surviving Bara films: A Fool There Was (1915, dir: Frank Powell)

[1] This anagram was alleged to have been the actresses’ own invention and the studio embraced it wholeheartedly creating a birth in the shadows of the Sphinx, a childhood in Egypt and exotic Parisian-Italian parentage. Tactics which enhanced the allure of the Cincinnati-born girl who wanted Hollywood to sit up and take notice.

[2] Carmen (1915, dir. Raoul, A. Walsh) Fox Film Corporation.

[3] Cleopatra (1917, dir. J. Gordon Edwards) Fox Film Corporation.

[4] Salome (1918, dir. J Gordon Edwards) Fox Film Corporation.

[5] Theda Bara functioned as a star persona serving as a ideological construct as detailed in Richard Dyer, Stars, (London:British Film Institute, 1998).

[6] A Fool There Was (1915, dir. Frank Powell) William Fox Vaudeville Company.

[7] Molly Haskell, From Reverence to Rape: The Treatment of Women in the Movies, (Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press, [1974] 1987) p103.

[8] Roberta Pearson, “O’er Step Not the Modesty of Nature: A Semiotic Approach to Acting in the Griffith Biographs, in: Zucker, C (ed) Making Visible the Invisible: An Anthology of Original Essays on Film Acting (Metuchen: New Jersey, 1990) pp1-27.

[9] Richard Dyer, White, (London & New York: Routledge, 1997 ) p

[10] Sumiko Higashi, Virgins, Vamps, and Flappers: The American Silent Movie Heroine (Canada: Eden Press, 1978) p58.

[11] Diane Negra “The Fictionalized Ethnic Biography: Nita Naldi and the Crisis of Assimilation” in: Gregg Bachman and Thomas J. Slater (eds) American Silent Film: Discovering Marginalized Voices, (USA: Southern Illinois University Press, 1997) pp 176-200 (179).

[12] Higashi (1978) p59.

[13] Mary Ann Doane, Femmes Fatales: Feminism, Film Theory, Psychoanalysis (London: Routledge, 1991) I.

[14] Janet Staiger, Bad Women: Regulating Sexuality in Early American (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995) p148.

[15] James Card, Seductive Cinema: The Art of the Silent Film (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota) p189.

[16] Diane Negra, “Immigrant Stardom in Imperial Stardom” in: Gregg Bachman and Thomas J. Slater (eds) American Silent Film: Discovering Marginalized Voices, (USA: Southern Illinois University Press, 1997)

[17] Romeo and Juliet (Dir: J. Gordon Edwards, 1916) Fox Film Corporation.

[18] E.T. Kirby, “The Delsarte Method: 3 Frontiers of Actor Training” in The Drama Review: TDR, Vol.16, No1, March 1972 pp55.69. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1144731?seq=1 [accessed 25 May 2012].

While a lot of The Perfect Candidate belongs to the political drama – gender politics are certainly at the heart of most films created within a place of female oppression like Saudi Arabia – this film feels more like an ode to the importance of cultural arts, perhaps even a tribute to the filmmaker’s own father, Abdul Rahman Mansour, who is a poet. Whether a conscious decision or due to her co-writer Brad Niemann’s input, the patriarch of this particular family is far gentler and more empathetic than we’re used to seeing onscreen – Maryam is never discouraged at any point by her Abi. As a result the male characters feel a lot more tangible within this narrative, with a variety of masculinities explored. It pulls from Maryam’s arc somewhat but as a result feels a little more balanced, ultimately the film begins and ends with the future. A woman. No longer hidden behind her niqab (if she so chooses).

While a lot of The Perfect Candidate belongs to the political drama – gender politics are certainly at the heart of most films created within a place of female oppression like Saudi Arabia – this film feels more like an ode to the importance of cultural arts, perhaps even a tribute to the filmmaker’s own father, Abdul Rahman Mansour, who is a poet. Whether a conscious decision or due to her co-writer Brad Niemann’s input, the patriarch of this particular family is far gentler and more empathetic than we’re used to seeing onscreen – Maryam is never discouraged at any point by her Abi. As a result the male characters feel a lot more tangible within this narrative, with a variety of masculinities explored. It pulls from Maryam’s arc somewhat but as a result feels a little more balanced, ultimately the film begins and ends with the future. A woman. No longer hidden behind her niqab (if she so chooses).

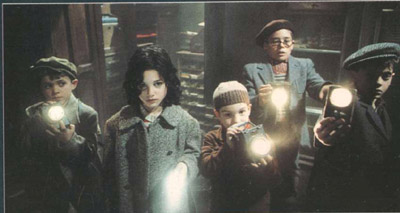

So begins two exposition stories, one weighted in reality the other in an alternative world where the outcome is dependent upon how the real infiltrates the imaginary. Roy’s epic tale is a story of six unlikely companions; buccaneer and explosives expert Luigi (Robin Smith), ex-slave Otta Benga (Marcus Wesley), Charles Darwin (Leo Bill), The Indian (Jeetu Verma), a Mystic (Julian Bleach) and The Blue Bandit (Emil Hostina) and follows their quest to defeat the evil Governor Odious (Daniel Caltagirone).

So begins two exposition stories, one weighted in reality the other in an alternative world where the outcome is dependent upon how the real infiltrates the imaginary. Roy’s epic tale is a story of six unlikely companions; buccaneer and explosives expert Luigi (Robin Smith), ex-slave Otta Benga (Marcus Wesley), Charles Darwin (Leo Bill), The Indian (Jeetu Verma), a Mystic (Julian Bleach) and The Blue Bandit (Emil Hostina) and follows their quest to defeat the evil Governor Odious (Daniel Caltagirone).