Can I Be Me‘s opening scenes take place on February 11th 2012 and we can hear the 911 dispatch call which was recorded on the night Whitney Houston, known as ‘Nippy’ to her family and friends, died alone aged 48. While there were dangerous levels of drugs found in her system, one of Whitney’s back-up singers tells us plainly, “She died of a broken heart.”

Whitney Elizabeth Houston was born in New Jersey on August 9th, 1963. Daughter of John and Cissy, and younger sister of Gary and Michael. Cissy would guide her, John would influence her and her brothers would provide the company when they did drugs together. Clive Davis would take her under his wing at 19 and create a pop icon – the best-selling black female vocalist since Aretha and Dionne (Warwick, who also happened to be a relative), and one who, according to Davis, would translate to a white audience.

Her debut album Whitney Houston sold 25 million copies. By 1988, the African American community felt she had sold out, her music had been ‘whitened’ and she was booed at the Soul Train Music Awards that same year (and the year after). Some say she never quite recovered from the rejection and she began seeing the “bad boy of R’n’B” Bobby Brown as, some have suggested, retaliation. They would later marry and the rest, as they say, is history. Well, not quite.

Footage takes us back to 1999 and the world tour Houston struggled to complete. The tour which would change the course of her career and, ultimately, her life. Combining home videos, archival footage and audio interviews, Nick Broomfield and Rudi Dolezal’s documentary is revealing without disrespect or exploitative intent; a frank portrait of a beloved and troubled artist. Nor does it shy away from the drug consumption, from teenage recreation, through the accidental overdoses, to the day it claimed her. This in itself addresses the level of apportioned blame aimed at Brown by the media.

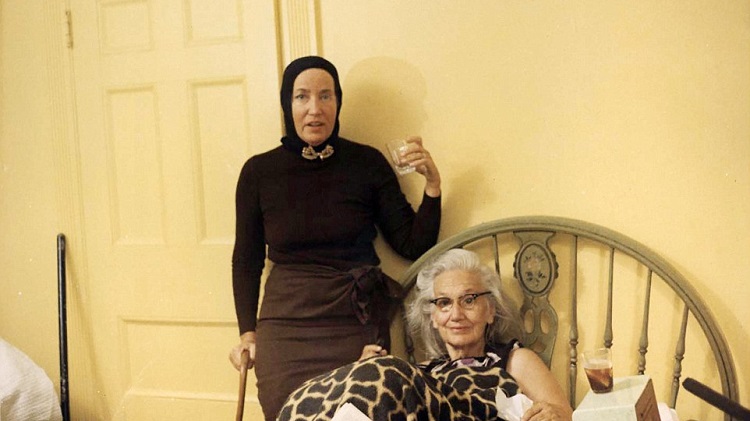

Their relationship was tumultuous to say the least, however, home videos depict a happy, loving couple with a similar goofy sense of humour while reality suggests there were three people in they marriage; Bobby, Whitney and Robyn Crawford. Crawford was Houston’s best friend and rumoured lover – Brown confirmed his wife’s bisexuality in his memoir – and from the footage depicted in this documentary, Brown and Crawford loathed each other. He appeared to be emasculated by her while she watched their competitive marriage hinge itself on drugs and alcohol; and yet both vied for Whitney’s love and attention. The real tragedy would be Bobby Kristina (March 4th 1993 – July 26th 2015), and this film is scathing in her parents’ neglect. Poor kid.

The situation reached breaking point when Houston’s bodyguard David Roberts compiled several reports on the singer’s habits and addictions, and his fears. He asked for help; an intervention but these pleas fell largely on deaf ears. How can you save somebody who doesn’t want to be saved? He maintains that all are responsible for Houston’s premature death. There are so many what-ifs offered up: if she had grown up in a less fiercely religious household… had she never touched drugs in the first place… had her father not claimed she owed him and sued her for $100 million. The biggest caveat of all is had she been able to live and love Robyn as she wanted, would she still be alive? Bobby Brown seems to think so but we are only offered this quote via an intertitle. He, Cissy, and Robyn are never interviewed by the filmmakers and thus it, along with Houston’s bisexuality, remains conjecture.

Can I Be Me is a candid, fascinating and heart-breaking documentary detailing – albeit within a very small window of time – the true toxic tragedy of fame and the toll of addiction, as is often the case of the truly gifted. Perhaps all of those around Whitney were in some way complicit in her destructive downfall but she was an addict, trapped within a brilliant, beautiful and troubled singer who only ever wanted to be herself, and sing. ‘Nippy’ changed the music industry and while some may have made their disapproval known once upon a time, she paved the way for the Mariahs, Beyoncés, Rihannas, and Leonas of this world, and a whole host of artists besides.

Where do broken hearts go – can they find their way home? In the case of this one, let’s hope so.