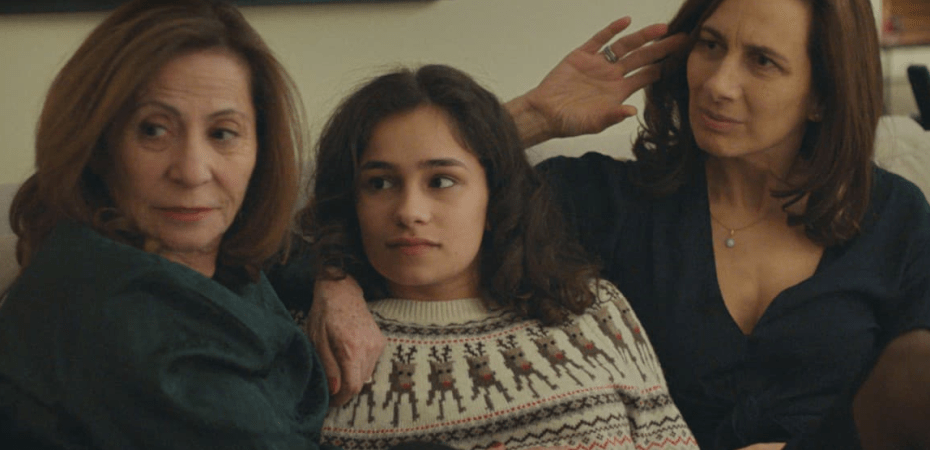

On Christmas Eve as the snow blankets the ground and buries car wheels deep in Montreal, Alex (Paloma Vauthier) and her Téta (Clémence Sabbagh) open the door to a parcel from Beirut. The delivery – addressed to Alex’s mother Maia (Rim Turkhi) – is initially turned away by the oldest matriarch who declares that “the past stinks”. The box contains cassette tapes of a life suppressed; Maia’s teenage years of the 70s and 80s in the wake of the sender’s death. Liza was Maia’s best friend and her dying wish, it appears, was to be reunited with her friend albeit through their memories, photos, notebooks and audio files. While Maia is too bereft to embrace her past, Alex finds the perfect opportunity to connect with a country she has never visited and a woman, her own mother, whom she barely knows.

With the aid of the box the audience learns, along with Alex, what a life is like during war – for most of us, we have not had to experience it – and bridging the generational divide however possible. Images literally come to life and interact with the music playing from the cassette recordings, for example, a memorable time-lapse sequence sound-tracked to Visage’s “Fade to Grey” while, you’ve guessed it, fading to grey. It may sound trite but it’s far from it as real-action bombs and gunfire burn holes in negative strips, and a potentially simplistic premise is fleshed out. It is incredibly evocative of a country ravaged by war and visually impressive, beautifully edited by Tina Baz.

Shifting between fantasy and reality, and with the help of flashbacks Alex enters her mother’s adolescence, her dreams and nightmares during the Lebanese Civil war and the loves and losses overcome during a tumultuous time. Alex, with the help of the late Liza, her Téta and the memory box is able to embrace the most important relationship of her life and see her mother not only as a woman and friend but with new understanding. The same goes for Maia and her own matriarch.

With such heavy hitting themes surrounding death, trauma, and abandonment, it is often the case for films depicting this sort of conflict to do so with earnestness and solemnity, however, Memory Box doesn’t do that. There were some 120,000 fatalities during 1975-1990 but not all perished in Beirut, many survived, lived and thrived and it is these people who are celebrated, the dead honoured in this intergenerational tale with women at the heart of its narrative.

To go forward, one must go back and sometimes reunite with your trauma and, in this case, a homeland which has been suppressed, wartime survival which has been denied, tragedy which has been compartmentalised, like a photo film that has never been processed in over thirty years. There is a compassion to Joreige, Hadjithomas and Gaëlle Macé’s screenplay which is non-judgemental and forgiving, especially in relation to Raja’s reappearance as an adult (Rabih Mroue). The first half may rely of a visual inventiveness and the image, yet, the second still manages to hit with emotional resonance and be deeply moving brimming with moments of levity.

Memory Box is a handcrafted gem by experimental filmmakers, Khalil Joreige and Joanna Hajithomas. Utilising their own photographs and journals written between 1982 and 1988 they create a visually inventive and accessible film which re-writes personal history, questions memory, its unreliability, and how it shapes the present. While visuals are particularly pop-arty and magazine-like, there is an overpowering resonance and meaningful juxtaposition. This is their memory box, made for their children, for whom the film is dedicated.

Memory Box is available to rent from all the usual places you can stream from.