Christopher Andrews’ directorial debut begins in the confines of a car as it races down a country lane at breakneck speed, a young woman Caroline (Grace Daly) is in the back and an older woman Peggy O’Shea (Susan Lynch) sits in the passenger seat. She’s had enough has Peggy, determined to leave the man who “terrifies” her, imploring ‘Mikey’ to “slow down”. This just ensures that the young driver, Michael, puts his foot down even more forcing the car out of his control.

Flash-forward twenty years as daylight gives way to darkness. Storm Noah is on its way, and Michael (Christopher Abbott) returns from tending his sheep to find his gate destroyed. His hands are crimson, fingers tinged blue from the cold weather as he and his dog Mac make their way inside. A phone call from the man they share a hill with, Gary Keeley (Paul Ready), causes Michael’s Ray (Colm Meaney) to fume and spew vitriol, as we are swiftly realise he is wan to do. Two of the O’Shea’s rams are dead on Keeley land and have to be destroyed. Rustlers are maiming sheep across the county, cutting the legs off livestock, destroying livelihoods and outsiders like “Poles or one of that shower…” are blamed for it. Little does Michael know the culprits are far closer to home and two rams is nothing compared with what is to come.

Andrews uses the farming crisis, boundary disputes and tourism-led gentrification in Ireland as a backdrop for his film (he also wrote the screenplay). Gary is in huge financial debt due to an investment of holiday homes, the building of which has stalled due to a large piece of farmland in the vicinity; the owners of which refuse to be displaced. Characters are at emotional and economic odds, the animosity historical. It goes way beyond land borders and boundaries for these two particular families – Caroline (Nora-Jane Noone) permanently scarred from the car accident seen in the prologue is now married to Gary and mother of Jack (Barry Keoghan) – with the two main protagonist sons in the middle of a tense situation neither asked for.

Filmed in Wicklow (the gorgeous pastoral landscapes do for Ireland what God’s Own Country did for Yorkshire), Bring Them Down unfolds like a neo-western but is steeped in Irish tragedy, as two sons reconcile family loyalty with the men that rule their respective roosts destroying the other at whatever cost. There are two very different patriarchs in Gary and Ray. One is a couple of decades older than the other and yet similarly unwise – probably bearing the brunt of their own fathers before them – breathtakingly noxious and incapable of breaking the cycle of bruising generational trauma and misguided vengeance. The film straddles the notion of tradition and modernity which is most impactful in how the two families communicate. The O’Sheas largely speak Gaelic to one another, the Keeleys English, which is turn signifies a larger territorial implication.

The film is split into two acts and the shifting of perspectives works brilliantly adding some nuance to a provocative and compelling drama which is relentlessly grim. Erratic camerawork that can be often out-of-focus only adds to the brutality onscreen, at times nausea-inducing, backed musically by a bass heavy soundtrack and the semi-persistent pound of a Gaelic drum. The performances are, for the most part, excellent. Meaney is as his name suggests and in the short amount of time he is on camera manages to convey the fear Ray instilled in his wife and child once upon a time. Noone provides fine support as one more underestimated, if somewhat reductive, woman looking to flee a marriage.

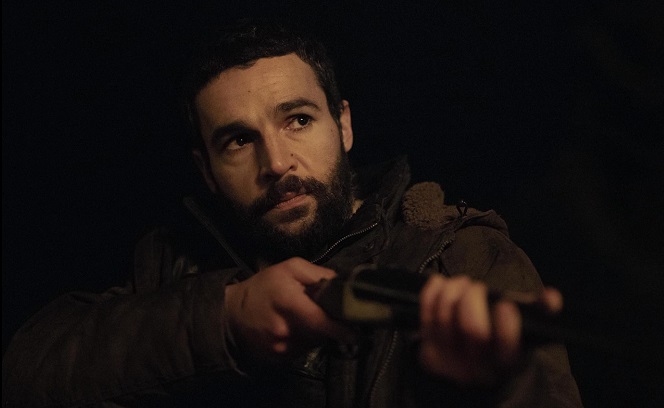

I am still not overly fond of Keoghan and his acting style, the twitching oddity and/or sociopathic man-child feels overdone at this point. For me, it is Abbott and Ready who carry this film. Their performances are as multi-layered as their Arran jumpers, padded gilets and waxed jackets. Brit Ready (hapless Kevin in Motherland) is a revelation as unpredictable Keeley who can blow a gasket just as easily as he’s wracked with sobs. Which leaves American Abbott – one of the best actors of his generation (see James White or any number of his supporting roles if you don’t believe me) – his accent is flawless, dipping in and out of Gaelic with an ease which belies his Connecticut upbringing. His complicated and stoic Michael internalises everything portraying a multitude with a silent stare, slump of the shoulders or sniff of the nose. This is a man constantly battling to do the right thing grappling to remain composed.

Bring Them Down is a suffocating and stressful watch depicting internal strife and the harsh, brutal and violent realities of a small rural community within which toxic masculinity breeds in all its contemptible shame.

The film is released in UK cinemas on Friday 7th February courtesy of MUBI.