Literature has, for the longest time, been considered the intellectually superior medium in opposition to cinema. This consensus (which is largely ill conceived) proves problematic when the two mediums are joined in the form of film adaptation. When a text is transferred to the screen, the fidelity of the adaptation is often utilised as the sole way in which to critique the altered work of literature. “[F]idelity criticism” according to Brian McFarlane, “depends on the notion of the text as having and rendering up to the (intelligent) reader a single, correct ‘meaning’ which the film-maker has either adhered to or in some sense violated or tampered with.”[1]This assumption proves problematic as no two people read a novel (or film) in the same way and there is no way to differentiate and announce that ‘the book was better than the film’ because each medium is separate and both remain autonomous, and “[…] characterised by unique and specific properties.”[2] Bluestone phrases adaptation best when he states:

What happens […] when the filmist undertakes the adaptation of a novel, given the inevitable, mutation, is that he does not convert the novel at all. What he adapts is a kind of paraphrase of the level – the novel viewed as raw material. He looks not to the organic novel, whose language is inseparable from its theme, but to characters and incidents which have somehow detached themselves from language and, like the heroes of folk legends, have achieved a mythic life of their own.[3]

However, Bluestone’s “paraphrasing or two ways of seeing” is not the only methodology of adaptation. There are many – more appropriate – modes to consider when looking to an adaptation, some of which will be explored in this essay. The intention of which is to analyse the adaptation of The Odyssey which was re-presented in the film form of O, Brother Where Art Thou?[4] Some may regard Homer’s poetic prose as a canonical piece of literature and by adapting it there is the suggestion that Ethan and Joel Cohen can re-acquaint the poem with those who have read it and thus forgotten it, or a new generation; those who are not as familiar with the original epic. By their admissions they saw to “retell The Odyssey” which they describe as the “funniest book ever chanted”, they believe that the finished product is “epic in scale, classic in scope, with dumb guys acting stupid” (Ethan and Joel Coen, 2002)[5]. On the simplest level they have fulfilled their expectations. Using Bluestone’s methodology as a starting point, the two mediums will be considered in their own right as poem and film, this will hopefully culminate in similarities and differences and how certain aspects of the book’s episodes are enunciated in the movie. Those elements that Brian McFarlane asserts are “intricate processes of adaptation […] [whose] effects are closely tied to the semiotic system on which they are manifested […]”[6].

The Odyssey’s narrative is told over twenty-four books and describes the saga of Odysseus in his quest for home. Books 1-4[7] (known as the Telemachid) introduce the reader to Odysseus’ son Telemachus who is campaigning for his father’s return to Ithaca. Following the Trojan War, Odysseus has been imprisoned on the island of Ogygia by the nymph Calypso and it is in a council of the Gods that Odysseus’ fate will be decided. Athene, the goddess of wisdom (and daughter of Zeus) implores the assembly to allow him safe passage from the island. Granted freedom, the poem’s hero builds a raft and drifts away from Ogygia, consequently he suffers Poseidon’s wrath, the god is still furious following the blinding of his son Polyphemus the Cyclops, at the hands of Odysseus and his men. Sent adrift by the storm Odysseus is rescued by Nausicaa, daughter of King Alcinous of Phaeacia who nurses him back to health and invites him to dine with the populace that evening. After arriving at the banquet Odysseus is asked to recount his narrative through ellipses and analepses (this is the section of the poem which most readers associate with The Odyssey). In these accounts he recalls the Lotus Eaters and the Cyclops (Book 9)[8]; Aeolus, the Laestrygonians (cannibalistic giants) and Circe (Book 10)[9]; Teiresias and his prophecies (Book 11[10]; the Sirens, Scylla and Charybdis, the killing of the Oxen of the sun occurs in Book 12[11] and sees Zeus destroying Odysseus’ sailing vessel, whereby Odysseus’ men die and shipwrecked, he washes up on the island of Ogygia (thereby returning to the present time). The remaining twelve episodes[12] present Odysseus in disguise as a beggar allowing him to return to Ithaca. Once there he is reunited with his son Telemachus and sets about the removal of Penelope’s suitors; these numerable men are murdered and Odysseus attempts to become master of his own home once more. However, before she completely trusts her husband’s true identity, Odysseus must complete Penelope’s test. Upon completion Odysseus is attacked by the vengeful Poseidon, until Zeus and Athene intervene (once again) and declare peace in Ithaca.

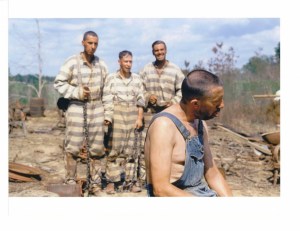

In Sullivan’s Travels[13] John Lloyd Sullivan (Joel McCrae) wishes to make his dream movie in Depression-era America, its title is O, Brother Where Art Thou? which the Coen brothers borrow wholesale. Their movie follows Ulysses Everett McGill (George Clooney) – Ulysses the Latin name for Odysseus – and his escape from a chain gang in Mississippi. Attached to his shackles are fellow prisoners Delmar (Tim Blake Nelson) and Pete (Coens regular John Turturro). Everett assigns himself leader of the outfit as “the man with the capacity for abstract thought” and leads them on a collective odyssey to unearth buried treasure. Their first stop is at Hogwallop farm in which Pete’s cousin Wash (Frank Collison) – perhaps a character allusion to Menelaus, as his wife Cora has “r-u-n-n-o-f-t” to “find answers” much like Helen of Troy. He removes their shackles and provides them with clean clothes, a hot meal and for Everett, hair pomade and a hair net. Attracted by Sheriff Cooley’s (Daniel Van Bargen) reward, Wash turns the trio over to the law and the three are on the run once more. Along the road the men pick up a Blues guitarist Tommy Johnson (Chris Thomas King) who is standing at crossroads having sold his soul to the devil. With Tommy’s help and accompaniment ‘Jordan Rivers and the Soggy Bottom Boys’ are formed and together they sing ‘into a can for $10 a-piece’ this song, it is later revealed becomes the hit of the thirties. The Sheriff thwarts their plan a second time, but this time they are ‘saved’ by an unlikely adversary, in the form of George “Baby Face” Nelson (Michael Badalucco). Two days into their journey they meet three brunettes (“Sireens”), one of whom allegedly transforms Pete into a toad, and then at a “fine eating establishment” Delmar and Everett meet Big Dan Teague (John Goodman), a salesman/conman who wears an eye patch. Eventually, after numerous mishaps Everett finds his way home and attempts to win back his wife Penny (Holly Hunter). Ancient Greece, Rome and Africa of the 1270s (these dates can be refuted) are shifted to Depression-era Deep South, the auditory channel of the film enunciates through visual codes the division of white and black, specifically on the chain gang at the film’s opening. Everett, Delmar and Pete are seemingly the only white prisoners in the hard labour prison but throughout the film allude to the notion of racial assimilation. They sing “negroe” songs, welcome musician Tommy Johnson into their fold without judgement (Johnson happens to be black) and are even mistaken for “miscegenated folk” when their identity is exposed as The Soggy Bottom Boys. In the literary text, there is a sea of great change following the aftermath of the Trojan war which is eventual peace. There is, however, still a democratic governing force in place, allowing the higher powers to dictate the impending future of Odysseus. Visually, this change is signified through the modification of the prison system. Pete, the second time around is able to remain unshackled and is even taken to a picture show. In addition, Menelaus “Pappy” O’Daniel (Charles Durning) and Homer Stokes (Wayne Duvall) are the candidates for Southern reform, and no, their names are not accidental. Their characterisations are intertextual links to The Iliad[14] and the battle between Sparta and Troy in which Agamemnon and Piriam battled for power. Troy’s secret weapon was the wooden horse, inside of which Odysseus and his army were contained ready to strike and defeat the Spartans. Pappy through his affiliation with Agamemnon (Menelaus was brother to Agamemnon) welcomes his ‘secret weapon’ to his political campaign as The Soggy Bottom Boys (Everett, Delmar, Pete and Tommy in disguise), the act which secures his stay in office as Governor.

The inclusion of Southern accents suggests the stereotype of socially backward Southerners. Delmar’s accent is soft and warm, he is the sensitive and thoughtful character and a direct link to Eumaeus, Odysseus’ faithful steward. Pete is the least intelligent of the trio and conforms to the Southern stereotype, he has bad teeth, drools and is a potential enunciation of Laertes, Odysseus’ father. This lonely, impotent character is restored to activity near the poems end, as is Pete when Everett and Delmar break him out of prison again. Everett has a less pronounced accent and his eloquence is noted because his associates lack it, however, he is a fast-talker a man blessed with the “gift of gab” and whose intelligence is shadowed by his utter lack of common sense and obvious narcissism. Much like the texts of the musical genre, diegetic music (in the form of songs) become narrative voices in their own right, they initiate sequences and scenes, and articulate that which cannot be seen. The songs themselves bear evidence of enunciation in that they attempt to preserve the musical rhythm in which Homer presents the episodic poem and the saga of Odysseus. These pieces of neo-traditional narrative country music and song, produced by another Coen collaborator T Bone Burnett also serve as cultural aspects of the movie. The film text depicts the way in which people lived at a specific point in history. A definitive time is never established, (although it is hinted at sometime in the thirties) signifiers place it around 1937-1938. Pete (now with an added fifty years on his prison sentence) mentions his release date now being 1987, while the real Robert Lee ‘Pappy’ O’Daniel (1890-1969) ran for Governor of Texas in 1938. The South, depicted in O, Brother Where Art Thou? juxtaposes the poor and middle classes’ lack of education with the crime wave of the 30s, while emphasising Southern hospitality (Mississippi is know as ‘the hospitality State’) and the importance of family.

The visual channel asserts the notion of self-reflexive story telling, the establishing and ending shots of the movie are filmed in black and white, as if to ascertain the story’s age and fiction, while the main body of the text sequences manipulate colour saturation. Every scene is sepia in tone supplementing the era in which it is set as well the state’s climate. Mississippi is a hot, humid and dusty State and the colour wash reiterates this and as much of the picture is filmed on location, there is an abundance of natural lighting and trees in the background and foreground of shots. While The Odyssey tells of Odysseus’ journey by boat and the sea, so O, Brother Where Art Thou? uses character names as signifiers to reference the water theme: Jordan Rivers, The Soggy Bottom Boys, and Vernon T. Waldrip. Pete may even be an allusion to St. Peter, who was a fisherman and of course, there is Delmar, his name translated from the original Spanish is “of the sea”. These are described as intertextual “connectives” (Riffaterre, 1990, p58) and will be discussed in more detail momentarily, first, to Wagner’s approach to adaptation.

Geoffrey Wagner’s “taxonomic approach” to adaptation relies upon three modes: transposition, commentary and analogy. Analogies, suggests Wagner, are films “that shift a fiction forward into the present, and make a duplicate story”[15]. It is also considered a measurement of the filmmaker’s skills, analogous attitudes and whether analogous rhetorical techniques are found within the text at hand. O, Brother Where Art Thou? follows the narrative of The Odyssey fairly closely (although there is a re-structuring of the plot events) and relies upon Ethan and Joel Coen’s skill as directors and screenwriters to incite rhetorical techniques in order to instil the films analogous form of adaptation. As two separate and different mediums, there is an inability to transpose fully a text to the screen. Instead there are a number of parallelisms in which character names and traits, even narrative events and themes can be preserved. For example, both poem and film commence in media res with Odysseus and Ulysses Everett McGill, men who are established as the hero and given narrative perspective within their own respective stories:

A hero [who] ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.[16]

Each story tells of an individual odyssey, one fraught with peril and innumerable obstacles on the way home. While neither character seeks fame nor fortune (Everett finds fortune three times but promptly loses it shortly thereafter), they both (eventually) find and sustain it. Odysseus through his storytelling and Everett through his singing talent. The character of Penelope is preserved in the form of Penny. Both characters are long-suffering wives to the protagonist(s) and initially expect their husbands to return to them, yet both characters grow tired of waiting and entertain the idea of re-marriage, together they are constructed as intelligent, astute and shrewd – the ideological “threat of woman”, which is scattered through signifiers in the diegesis. In one scene Everett calls his wife a “lying succubus” which is enunciated through Penny’s daughters – she has seven. In having her children, Penny is able to secure marriage to her “suitor” Vernon T. Waldrip (Ray McKinnon) who will support the family with his “bonafide” prospects. This “threat” of females is also expressed in the Sirens satellite, there are three in all (one serves as reference to Circe, and supposedly transforms Pete into a toad). Other recurring themes include the element of masquerade, Odysseus and Everett must disguise themselves as beggars in order to win back their wives. Odysseus attempts to avoid confrontation with Poseidon, Everett on the other hand has escaped from the chain gang and is hotly pursued by Sheriff Cooley who is a possible Poseidon/Zeus/Hades amalgam. While there is never an allusion to a son, Cooley’s anger stems from the transgression of law, a human institution which he is affiliated with and one he believes in. He appears to conjure forks of lighting in the darkness, like Zeus, and the flames of fire that are reflected in his dark lenses suggests an affinity with the underworld. A further exploration is the notion of hospitality – this is a fundamental feature of Homeric society, while Odysseus is welcomed into Phaecia with open arms, so Everett and his friends are treated to Southern hospitality, warm food, fresh clothes and even invited along to a bank robbery, during the satellite in which they meet George ‘Baby Face’ Nelson.

“Commentary”, states Wagner is “where an original is taken and purposely altered in some respect [perhaps] a re-emphasis or re-structure”[17]. What is commented upon in both texts is the opening dialogue (the intertitle in the film quotes) “Oh Muse! / Sing in me, and through me tell the story / Of that man skilled in all the ways of contending / A wanderer, harried for years on end”. This narrative immediately sets the scene for the odyssey of a simple man returning home after a prolonged absence, a man who is the driving force of the narrative with hubris (great pride and vanity) – enunciated as Dapper Dan hair pomade and Everett’s obsession with his hair. What is most commented upon in the film (and poem) is the fight of oppression – sexual, racial and social, the upholding of a democratic society and a world attempting to cope with the affects of post-war, the Trojan War (approximate end, 1250) is re-emphasised as World War I (1914-1919).

There are, however elements of this adaptation which can be regarded as analogous started with the complete reworking (and re-structuring) of Odysseus’ epic nine year saga, from thirteenth century Greek mythology to the South of twentieth century America in which the narrative episodes unfold over four days. Here, multiple characters are given subjectivity rather than the extradiegetic and intradiegetic narrators of Homer and Odysseus or the heterodiegetic narrator(s) embedded within the tales of the Lotus-Eaters, the Cyclops and the Sirens. Each of these stories serves as hypodiegetic narratives, “below the diegesis”[18] in order to supplement the overarching story of the Odysseus/Everett’s safe passage home – although this is not actually revealed until near the movie’s climax as a satellite. Pete has now informed the Sheriff of their plan to “seek the treasure” leaving Everett safe to confess the treasure’s lack of existence, this minor plot event serves the proceeding kernel. Everett and Pete fight culminating in a fall which leads to the discovery of Charybdis (the many headed monster of Book 12) pronounced as a Klu Klux Klan mob. This kernel re-establishes ties to certain characters and re-introduces them into the diegesis. Homer Stokes is the leader of the KKK and intends to lynch Tommy Johnson, an attempt at ethnic cleansing (or allusion to the Holocaust, perhaps), Everett, Delmar and Pete have to save to him, forgetting that they faces are camouflaged in dirt. This is also the scene in which source intertexuality is utilised, specifically the return of “Big Dan” – his initial introduction is a narrative kernel and major plot event in the poem – Odysseus in his blinding of Polyphemus angers the giant’s father Poseidon, The God of the Sea’s wrath causes Odysseus to land on Phaeacia, the place where his odyssey is recounted. As the film is based within a verisimilar environment, “Big Dan” of course is a “regular” sized man, but camera angles (low and tilted) defy logic and represent him as “larger-than-life”, while his limbs are manipulated by diegetic sound effects which add weight and gravitas to Goodman’s performance as an ironized form of the “con-man”. The implied author of his film is the director and screenwriter (in this case they are two and the same) the narrator on the other hand is “a heterogeneous mechanical and technical instrument constituted by a large number of different components”[19]. The filmmakers’ use of dissolves, fades and wipes (which often resemble the turning of a page) are to offer visual punctuation, as well as display a cinematic technique of storytelling.

In Book 9, Odysseus utters the following: “Nothing so sweet is as our country’s earth / And joy of those from whom we claim our birth”[20] – these lines are enunciated through the cultural context of art, film to be precise. The three heroes stare down on the configuration of KKK members and seizing the opportunity they knock three guards unconscious and procure their attire. This scene is taken from The Wizard of Oz[21], in which Scarecrow, Lion and Tin-Man rescue Dorothy from the clutches of the Wicked Witch, Dorothy’s mantra of “there’s no way place like home” is signifier of this parody. Big Dan eventually sniffs out the trio, in a reference to Jack and the Beanstalk, Dan can literally smell the hair pomade of a vain man and a fight ensues, Everett, Delmar and Pete are successful in their rescue of Tommy and victorious over the “Cyclops” (Big Dan). Their black faces cause confusion and this scene serves as another satellite when Homer Stokes is exposed as the racist pig he is (Wayne Duvall is porcine in appearance as Stokes and serves as an allusion to Book 10, in which Circe transforms Odysseus’ men into swine[22].

O, Brother… appears to be one large fabula interwoven with a vast selection of intertextual references and allusions, parodies and transformations, some of which have been discussed thus far. However, to completely understand an adaptation is to recognise and potentially comprehend how intertexuality can enhance literary understanding. Homer’s Odyssey makes several allusions to the Trojan War and its casualties, this is a fragile intertextual connective as there is little clarification to be made (The Iliad precedes The Odyssey in time and space, its narrative – the Trojan War). With O, Brother Where Art Thou? the reader perceives that something is missing from the text and checks the reference As previously discussed, there is a high level of source intertexuality and context intertextuality, this may label the movie as a bricholage but does not aid in a final conclusion: the film as commentary or analogy. The film technique is quintessentially ‘Coen’ and this is signposted through the use of camera (via director of cinematography, Roger Deakins), mise-en-scène, the actors who have collaborated with the filmmakers before: John Goodman (The Big Lebowski, Joel Coen, 1998), Holly Hunter (Raising Arizona, Joel Coen, 1987) and John Turturro (Barton Fink, Joel Coen, 1991) and the performances they evoke, all are exaggerated, mythic and surreal in characterisation.

As a conservative state, the Mississippi depicted in the film is particularly religious which may offer an explanation for the “Lotus-Eaters” enunciation, in which a congregation are baptised, their sins and transgressions are washed away. Baptism, according to the Coens, is the holy Lotus-Flower. This sequence is a narrative satellite which is introduced by a gospel chorus who sing ‘Down to the River to Pray’. This spiritual aspect to the film (the poem did contain many Gods in many forms) is also seen in a recurring cross motif displayed within the diegesis, one of these crosses is presented in the form of crossroads. At them the trio of protagonists pick up guitarist Tommy Johnson, Tommy is a reference to historical Blues guitarist Robert Johnson, who performed the following lyrics “[…] standing at the crossroads I tried to flag a ride […] I said, hello, Satan, I believe it’s time to go” (Cline)[23]. Tommy’s introduction into the mythic discourse, acts as a narrative kernel integral to the overall sjuzet, without Tommy the trio would not have become The Soggy Bottom Boys at WEZY station, and preventing his death ultimately leads to a pardon from the Governor.

According to tradition, Homer was a wandering blind poet and is alluded to at the narrative’s beginning and conclusion of the film, in the form of the blind seer who prophesises the odyssey. He helps commence the story and plot as well as closure, conforming to the Aristotelian notion of narrative, in which a third person narrator initiates a story. In this case the seer/Homer withdraws and allows the characters to interact with each other and ultimately tell the story[24]. The radio controller at WEZY radio station (Aeolus) is also blind, he ‘composes’ just like the bard, and aids in the success of Jordan Rivers and the Soggy Bottom Boys and the recording of their iconic song ‘Man of Constant Sorrow’. This acknowledges the Mississippi patron saint (Our Lady of Sorrows) and even references autobiographical information of George Clooney (he too bid “farewell to old Kentucky where he was born and raised”) – although, this may be taking intertexuality a tad too far. After surviving the damming of the Mississippi, the film’s narrative draws to a close, ending Everett’s odyssey. He has overcome many obstacles including ‘Penny’s test’, in which he has to recover her wedding ring from the drawer in her bureau (in the middle of the damming). He remarks that ‘all’s well that ends well’, an obvious Shakespearean reference which is best enunciated in the following lines from the play; “[…] when thou canst get the ring upon my finger, which never shall come off, and show me a child begotten of thy body that I am father to, then call me husband […].[25]

Film adaptations, as this project has attempted to show, is a complex process, one which cannot be explained away by fidelity criticism. In taking Homer’s Odyssey, the Coen brothers have created a commentary (with a questionable analogous rhetoric) of the epic poem; a ‘paraphrase’, one rich in source and contextual intertextuality as well as hypodiegetic narratives and enunciation which makes for a memorable film, from beginning to end. The adaptation improves (visually) upon the initial work in its transference of setting and ultimately makes the saga much more accessible to a modern audience while restoring the pathos and irony of the original, Odysseus enthrals an audience with his words, while Ulysses Everett McGill beguiles with his music. Homer draws the most appropriate conclusion to this essay, “[…] You move our eyes / With form, our minds with matter, and our ears / With elegant oration, such as bears / A music in the order’d history […]” (Book 11, p220: 493-496).[26]

[1] McFarlane, B. Novel to Film: An Introduction to the Theory of Adaptation. UK: Clarendon Press. (1996, p8).

[2] Bluestone, G. Novels Into Film. USA: John Hopkins University ([1957] 2003, p6).

[3] Ibid p8

[4] Joel Coen cited in Cohen, M, “O Brother Where Art Thou?” (2000)

http://www.sensesofcinema.com/contents/00/11/obrother.html [accessed 27th April 2007]

[5] O Brother Where Art Thou? [DVD Extras)] (2000, dir. Joel Coen).

[6] McFarlane (1996, p20).

[7] Homer, The Odyssey, trans. George Chapman. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Limited (1614-1615, pp1-95).

[8] Ibid. pp167-186.

[9] Ibid. pp187-205.

[10] Ibid, pp207-229

[11] Ibid. pp231-248

[12] Ibid. pp249-474

[13] (1941, dir. Preston Sturges).

[14] Homer, The Iliad, trans. George Chapman. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Limited (1598-1611).

[15] Wagner, G. The Novel and the Cinema. USA: Fairleigh-Dickinson University (1975, p226).

[16] Campbell, J. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. London: Fontana Press (1993, p30).

[17] Wagner (1975, 223).

[18] Lothe, J. Narrative in Fiction and Film. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2000, pp32-34)

[19] Ibid, p30.

[20] Homer, (p170: 63-64).

[21] (1939, dir. Victor Fleming).

[22] Homer, (p196: 23-329).

[23] Cline, J “American Myth Today: O, Brother Where Art Thou? and the Language of Mythic Space.” (2005) http://xroads.virginia.edu/-ma05/cline/obrother/free6/obrother5.htm [accessed: 2nd April 2007].

[24] Berger, A. A. Narratives in Popular Culture, Media and Everyday Life. USA: SAGE Publications (1997, p20).

[25] Shakespeare, W (1603) All’s Well That Ends Well In: Proudfoot, Thompson & Kastan (eds) The Arden Shakespeare Complete Works. London: The Arden Shakespeare, (2005, pp89-119).

[26] Homer, (p220: 493-496).