Man of a Thousand Faces begins with the following cue: “On August 27 1930, the entire Motion Picture industry suspended work to pay tribute to the memory of one of its great actors. This is his story.” Except, well, it’s not. It’s the ‘Hollywood’ version steeped in melodrama and all a little dull.

At the Universal studio lot, the flag flies at half-mast as Irving Thalberg (played by the late Robert Evans, sans perma-tan) makes his own tribute to “The phantom of the opera.” In actuality, work was not suspended but a two minute silence was conducted in the wake of Lon Chaney’s death – nor were his most successful films made at Universal… This film starts as it means to go on, dramatising and conflating the life of an extremely private man who, if history books are to be believed, would have shunned even this mediocre production.

The biopic begins with the obligatory flashback which will serve the overarching narrative and then loop back around; aligning childhood, trauma and tragedy which is seemingly how it wants to establish Chaney (James Cagney). It traces his career from the Vaudeville stage to the cinema screen and admirably attempts to squeeze 30 years into 122 minutes, perhaps had the film been cast differently it may just have worked.

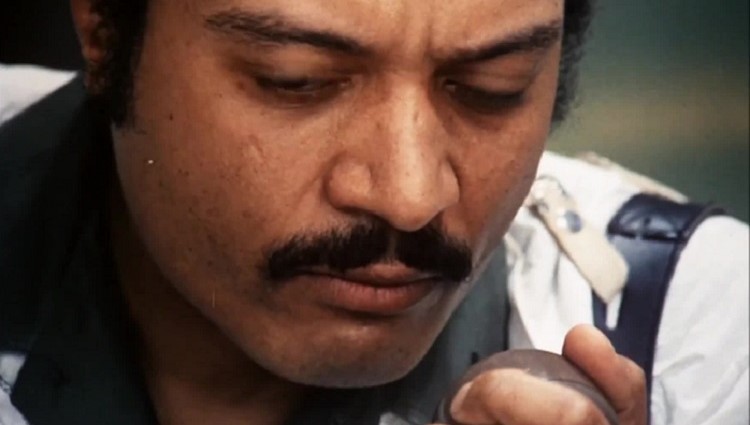

As talented as Cagney arguably was, there’s no way he can pull off aged 22 at 56 convincingly. Not to mention the physical limitations; a tall sinewy figure with a distinctive growl never really translates to a chipper Irish-American barely reaching 5’7”. Star personas were prevalent during the studio system and it’s fair to say, Cagney was horribly miscast nor did he have the lithe grace Chaney exhibited or the creepy melancholy.

If there’s one word used to describe the tone of the film, it is tragedy, as it prefers to add weight to the man’s alleged suffering than his film career. Hammering home his deaf-mute parents, hitting child abandonment and the dissolution of his marriage along the way, to having to place son Creighton in an orphanage and then, well, death. It’s all rather dreary; at odds with the sweeping epic soundtrack and the man whose early career began in Vaudeville and making people laugh. Why his parents’ deafness defines him or them, for that matter, appears to be a sign of the times – as for when that is the film does little to quantify. Creighton (he who would become Lon Chaney Jr.) is the only real evidentiary passage of time as the part is split between four actors (Dennis Rush, Rickie Sorensen, Robert Lydon and Roger Smith) each older than the next. None of which is helped by the occasional fifties-looking costuming.

Before his ‘big break’ as a lead, Chaney worked tirelessly and took every job he could, often making himself over and disguising his natural attributes depending on what was required on the call sheet. His ground-breaking make-ups led the way for the likes of Jack Pierce. Bud Westmore, Dick Smith, and, of course, Rick Baker among many, many others. It was then that casting agents began to take notice and he was cast in The Miracle Man thanks to his ability to twist and coil his body into unnatural positions. This would lead to arguably his greatest roles: The Phantom of the Opera and The Hunchback of Notre Dame in which he gravitated, yet again, to the tortured and afflicted depicting the tormented empathy of Quasimodo. Cagney tries but it’s hard not to see Cagney playing ‘Cagney’ imitating Chaney, or ‘Chagney’ if you will.

Obviously, given the decades between meant different make-up processes and evolution of the prosthetic. The make-up recreations in Man of a Thousand Faces are pretty awful given that Westmore et al would have used more modern supplies and they are still nowhere as convincing as Chaney and his ‘crude’ materials. Eagle-eyed viewers will also notice that camera-angles vary in relation to the original films, they’re not quite as polished.

It’s not all terrible, there are some high points. The father-son relationship shines and the performances from the actors who played the young(er) Creighton are lovely. These moments highlight Chaney’s love of mime and character, donning wigs and a false nose to “show” his son a bedtime story. The use of sign language is refreshingly brilliant for a film as old as this, when communicating it’s all about the face which for Lon Chaney it was. His.

He worked in cinema from 1914-1930 with 100 of his 157 films either lost or destroyed. It’s a missed opportunity that the 2000 documentary, The Man of a Thousand Faces narrated by Sir Kenneth Branagh isn’t included in the extras here. However, if Chaney holds an interest for you, seek it out, it’s really informative and one gets to see the original performer rather than a shallow impersonation. While the film never quite reaches the heights expected, the transfer is stunning. It is clear and crisp with very little residing grain which serve the make-up replicas and those stark chiaroscuro shadows which ‘Chagney’ often lurks within.

Lon Chaney died from a throat haemorrhage brought on my complications from the cancer that he was diagnosed with years earlier. An almost karmic fate for a versatile entertainer who sought silence both on stage and screen – his last film (a remake of Browning’s The Unholy Three) was his only speaking role – and has been revered ever since.

Disc Extras

Commentary by Tim Lucas – this is highly informative and provides great education for those unfamiliar with Chaney and his work and those that are interested in their broadening their knowledge. Lucas provides lots of information and titbits, paying particular attention to historical context – something the film sorely lacks.

The Man Behind a Thousand Faces: Kim Newman on Lon Chaney (20:52) Filmed in a cluttered room full of DVDs and books, Kim in his signature red waistcoat and cravat discusses the silent stars of Hollywood’s heyday including Chaplin, Garbo, Valentino and of course Chaney. Newman’s brief foray into the topic is not overly focussed and feels more conversational in tone which is a great contrast to the slightly more scripted and academic commentary. He maintains that Chaney lingers long in the cultured memory “and without Chaney’s make up Karloff and Lugosi would have contrived to play gangsters, and never Universal monsters (though, I’m sure Jack Pierce would have argued with that). He also thinks Cyrano de Bergerac was the role Chaney was made for but never got the chance to play. The chat is intercut with clips from the films and sadly, ends rather abruptly.

Theatrical Trailer (1:33) – It’s always worth watching the film’s theatrical trailer if only to see the original footage prior to the restoration process, and the extent of the transfer and clean up.

Image Galleries – These include 82 slides of production stills which show the costumes and make-ups in greater detail (not always a pro) and give more opportunity to see Bud Westmore’s clunky recreations albeit all in black and white. In addition to the slides, there are 18 posters and lobby cards in both monochrome and colour from all over the world including France, Spain, Germany and Russia.